Approximate time: 90 minutes

Learning Objectives:

- Construct QC metrics and associated plots to visually explore the quality of the data

- Evaluate the QC metrics and set filters to remove low quality cells

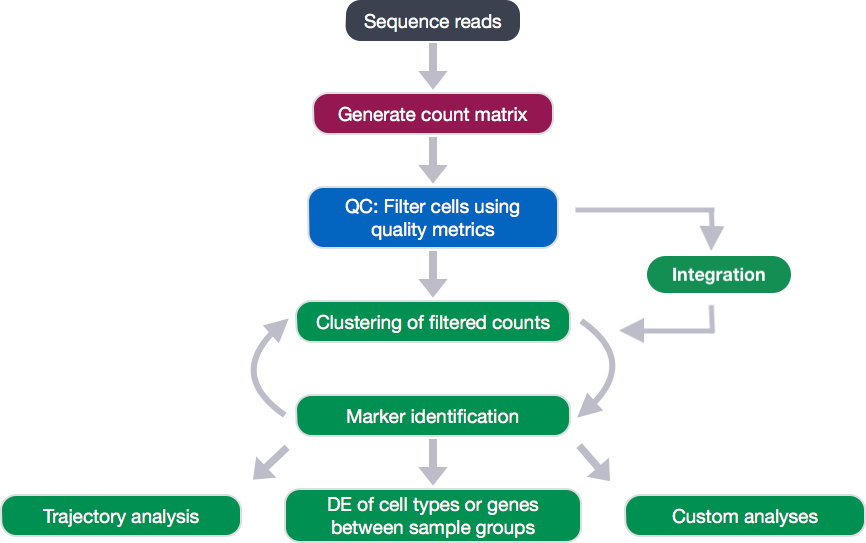

Single-cell RNA-seq: Quality control

Each step of this workflow has its own goals and challenges. For QC of our raw count data, they include:

Goals:

- To filter the data to only include true cells that are of high quality, so that when we cluster our cells it is easier to identify distinct cell type populations

- To identify any failed samples and either try to salvage the data or remove from analysis, in addition to, trying to understand why the sample failed

Challenges:

- Delineating cells that are poor quality from less complex cells

- Choosing appropriate thresholds for filtering, so as to keep high quality cells without removing biologically relevant cell types

Recommendations:

- Have a good idea of your expectations for the cell types to be present prior to performing the QC. For instance, do you expect to have low complexity cells or cells with higher levels of mitochondrial expression in your sample? If so, then we need to account for this biology when assessing the quality of our data.

Generating quality metrics

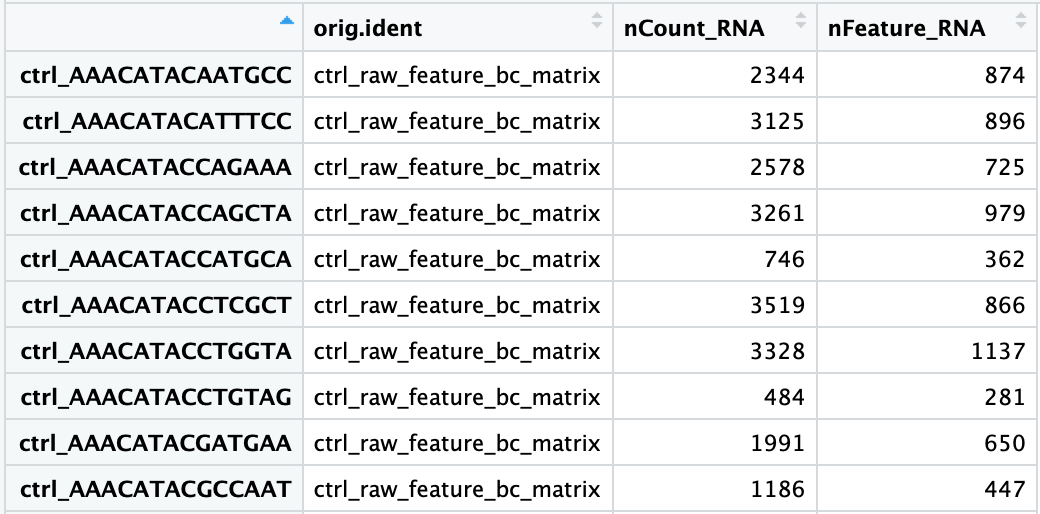

Remember that Seurat automatically creates some metadata for each of the cells:

# Explore merged metadata

View(merged_seurat@meta.data)

The added columns include:

orig.ident: this often contains the sample identity if known, but will default toprojectas we had assigned itnCount_RNA: number of UMIs per cellnFeature_RNA: number of genes detected per cell

We need to calculate some additional metrics for plotting:

- number of genes detected per UMI: this metric with give us an idea of the complexity of our dataset (more genes detected per UMI, more complex our data)

- mitochondrial ratio: this metric will give us a percentage of cell reads originating from the mitochondrial genes

The number of genes per UMI for each cell is quite easy to calculate, and we will log10 transform the result for better comparison between samples.

# Add number of genes per UMI for each cell to metadata

merged_seurat$log10GenesPerUMI <- log10(merged_seurat$nFeature_RNA) / log10(merged_seurat$nCount_RNA)

Seurat has a convenient function that allows us to calculate the proportion of transcripts mapping to mitochondrial genes. The PercentageFeatureSet() will take a pattern and search the gene identifiers. For each column (cell) it will take the sum of the counts slot for features belonging to the set, divide by the column sum for all features and multiply by 100. Since we want the ratio value for plotting, we will reverse that step by then dividing by 100.

# Compute percent mito ratio

merged_seurat$mitoRatio <- PercentageFeatureSet(object = merged_seurat, pattern = "^MT-")

merged_seurat$mitoRatio <- merged_seurat@meta.data$mitoRatio / 100

NOTE: The pattern provided (“^MT-“) works for human gene names. You may need to adjust depending on your organism of interest. If you weren’t using gene names as the gene ID, then this function wouldn’t work. We have code available to compute this metric on your own.

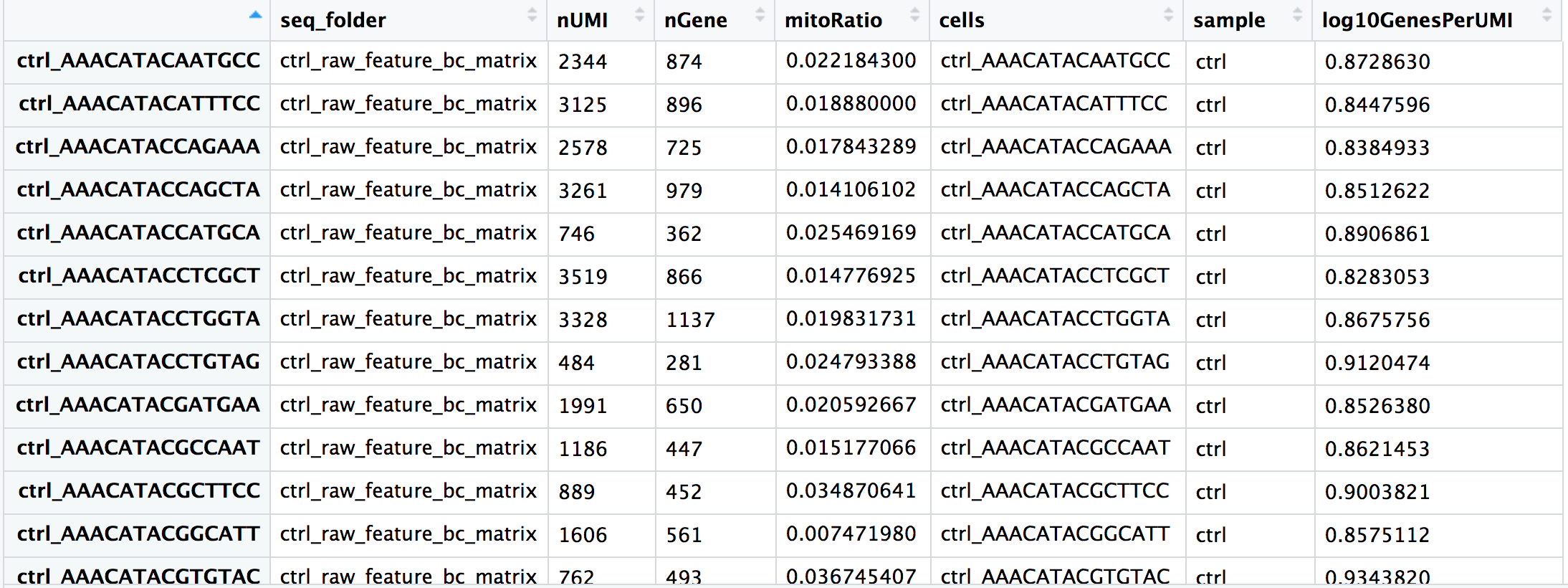

We need to add additional information to our metadata for our QC metrics, such as the cell IDs, condition information, and various metrics. While it is quite easy to add information directly to the metadata slot in the Seurat object using the $ operator, we will extract the dataframe into a separate variable instead. In this way we can continue to insert additional metrics that we need for our QC analysis without the risk of affecting our merged_seurat object.

We will create the metadata dataframe by extracting the meta.data slot from the Seurat object:

# Create metadata dataframe

metadata <- merged_seurat@meta.data

You should see each cell ID has a ctrl_ or stim_ prefix as we had specified when we merged the Seurat objects. These prefixes should match the sample listed in orig.ident. Let’s begin by adding a column with our cell IDs and changing the current column names to be more intuitive:

# Add cell IDs to metadata

metadata$cells <- rownames(metadata)

# Rename columns

metadata <- metadata %>%

dplyr::rename(seq_folder = orig.ident,

nUMI = nCount_RNA,

nGene = nFeature_RNA)

Now, let’s get sample names for each of the cells based on the cell prefix:

# Create sample column

metadata$sample <- NA

metadata$sample[which(str_detect(metadata$cells, "^ctrl_"))] <- "ctrl"

metadata$sample[which(str_detect(metadata$cells, "^stim_"))] <- "stim"

Now you are all setup with the metrics you need to assess the quality of your data! Your final metadata table will have rows that correspond to each cell, and columns with information about those cells:

Saving the updated metadata to our Seurat object

Before we assess our metrics we are going to save all of the work we have done thus far back into our Seurat object. We can do this by simply assigning the dataframe into the meta.data slot:

# Add metadata back to Seurat object

merged_seurat@meta.data <- metadata

# Create .RData object to load at any time

save(merged_seurat, file="data/merged_filtered_seurat.RData")

Assessing the quality metrics

Now that we have generated the various metrics to assess, we can explore them with visualizations. We will assess various metrics and then decide on which cells are low quality and should be removed from the analysis:

- Cell counts

- UMI counts per cell

- Genes detected per cell

- UMIs vs. genes detected

- Mitochondrial counts ratio

- Novelty

What about doublets? In single-cell RNA sequencing experiments, doublets are generated from two cells. They typically arise due to errors in cell sorting or capture, especially in droplet-based protocols involving thousands of cells. Doublets are obviously undesirable when the aim is to characterize populations at the single-cell level. In particular, they can incorrectly suggest the existence of intermediate populations or transitory states that do not actually exist. Thus, it is desirable to remove doublet libraries so that they do not compromise interpretation of the results.

Why aren’t we checking for doublets? Many workflows use maximum thresholds for UMIs or genes, with the idea that a much higher number of reads or genes detected indicate multiple cells. While this rationale seems to be intuitive, it is not accurate. Also, many of the tools used to detect doublets tend to get rid of cells with intermediate or continuous phenotypes, although they may work well on datasets with very discrete cell types. Scrublet is a popular tool for doublet detection, but we haven’t adequately benchmarked it yet. Currently, we recommend not including any thresholds at this point in time. When we have identified markers for each of the clusters, we suggest exploring the markers to determine whether the markers apply to more than one cell type.

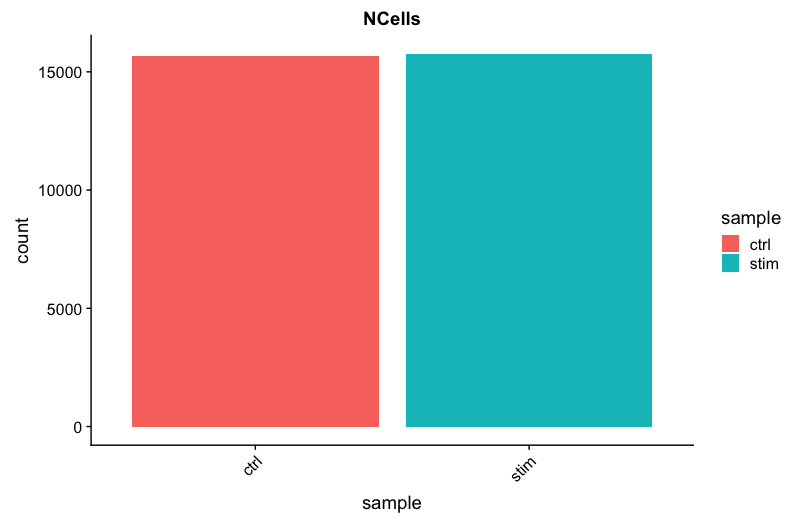

Cell counts

The cell counts are determined by the number of unique cellular barcodes detected. For this experiment, between 12,000 -13,000 cells are expected.

In an ideal world, you would expect the number of unique cellular barcodes to correpsond to the number of cells you loaded. However, this is not the case as capture rates of cells are only a proportion of what is loaded. For example, the inDrops cell capture efficiency is higher (70-80%) compared to 10X which can drop is between 50-60%.

NOTE: The capture efficiency could appear much lower if the cell concentration used for library preparation was not accurate. Cell concentration should NOT be determined by FACS machine or Bioanalyzer (these tools are not accurate for concentration determination), instead use a hemocytometer or automated cell counter for calculation of cell concentration.

The cell numbers can also vary by protocol, producing cell numbers that are much higher than what we loaded. For example, during the inDrops protocol, the cellular barcodes are present in the hydrogels, which are encapsulated in the droplets with a single cell and lysis/reaction mixture. While each hydrogel should have a single cellular barcode associated with it, occasionally a hydrogel can have more than one cellular barcode. Similarly, with the 10X protocol there is a chance of obtaining only a barcoded bead in the emulsion droplet (GEM) and no actual cell. Both of these, in addition to the presence of dying cells can lead to a higher number of cellular barcodes than cells.

# Visualize the number of cell counts per sample

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(x=sample, fill=sample)) +

geom_bar() +

theme_classic() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, vjust = 1, hjust=1)) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust=0.5, face="bold")) +

ggtitle("NCells")

We see over 15,000 cells per sample, which is quite a bit more than the 12-13,000 expected. It is clear that we likely have some junk ‘cells’ present.

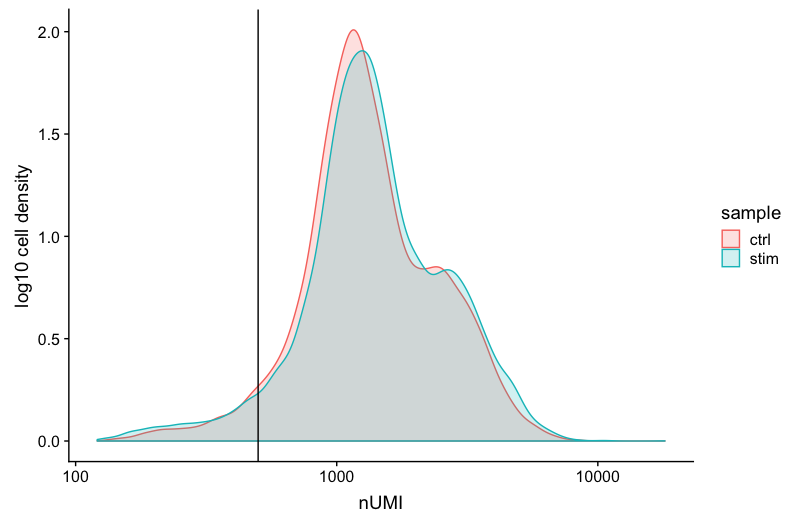

UMI counts (transcripts) per cell

The UMI counts per cell should generally be above 500, that is the low end of what we expect. If UMI counts are between 500-1000 counts, it is usable but the cells probably should have been sequenced more deeply.

# Visualize the number UMIs/transcripts per cell

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(color=sample, x=nUMI, fill= sample)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2) +

scale_x_log10() +

theme_classic() +

ylab("Cell density") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 500)

We can see that majority of our cells in both samples have 1000 UMIs or greater, which is great.

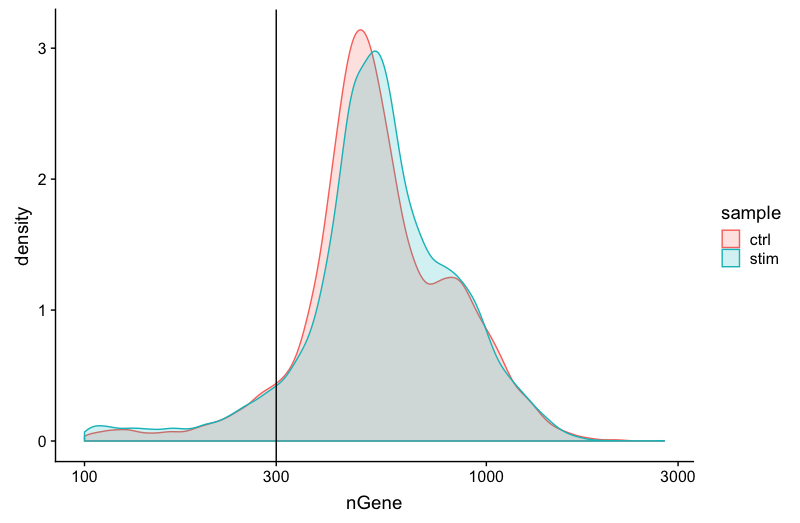

Genes detected per cell

We have similar expectations for gene detection as for UMI detection, although it may be a bit lower than UMIs. For high quality data, the proportional histogram should contain a single large peak that represents cells that were encapsulated. If we see a small shoulder to the right of the major peak (not present in our data), or a bimodal distribution of the cells, that can indicate a couple of things. It might be that there are a set of cells that failed for some reason. It could also be that there are biologically different types of cells (i.e. quiescent cell populations, less complex cells of interest), and/or one type is much smaller than the other (i.e. cells with high counts may be cells that are larger in size). Therefore, this threshold should be assessed with other metrics that we describe in this lesson.

# Visualize the distribution of genes detected per cell via histogram

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(color=sample, x=nGene, fill= sample)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2) +

theme_classic() +

scale_x_log10() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 300)

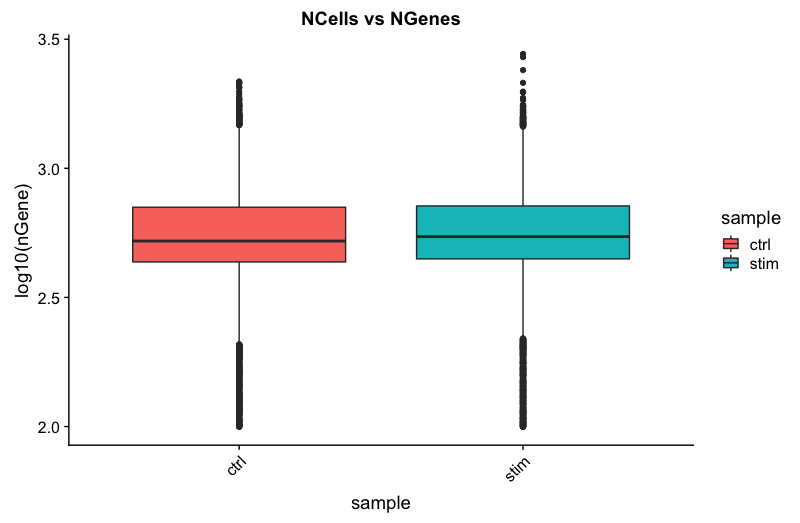

# Visualize the distribution of genes detected per cell via boxplot

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(x=sample, y=log10(nGene), fill=sample)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_classic() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, vjust = 1, hjust=1)) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust=0.5, face="bold")) +

ggtitle("NCells vs NGenes")

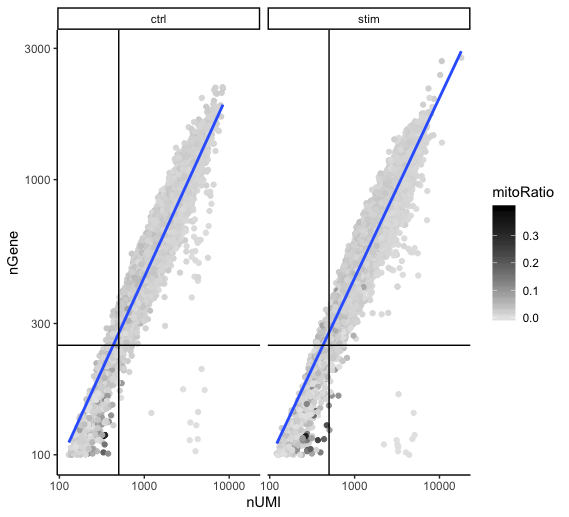

UMIs vs. genes detected

Two metrics that are often evaluated together are the number of UMIs and the number of genes detected per cell. Here, we have plotted the number of genes versus the numnber of UMIs coloured by the fraction of mitochondrial reads. Mitochondrial read fractions are only high (light blue color) in particularly low count cells with few detected genes. This could be indicative of damaged/dying cells whose cytoplasmic mRNA has leaked out through a broken membrane, and thus, only mRNA located in the mitochondria is still conserved. These cells are filtered out by our count and gene number thresholds. Jointly visualizing the count and gene thresholds shows the joint filtering effect.

Cells that are poor quality are likely to have low genes and UMIs per cell, and correspond to the data points in the bottom left quadrant of the plot. Good cells will generally exhibit both higher number of genes per cell and higher numbers of UMIs.

With this plot we also evaluate the slope of the line, and any scatter of data points in the bottom right hand quadrant of the plot. These cells have a high number of UMIs but only a few number of genes. These could be dying cells, but also could represent a population of a low complexity celltype (i.e red blood cells).

# Visualize the correlation between genes detected and number of UMIs and determine whether strong presence of cells with low numbers of genes/UMIs

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(x=nUMI, y=nGene, color=mitoRatio)) +

geom_point() +

scale_colour_gradient(low = "gray90", high = "black") +

stat_smooth(method=lm) +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_y_log10() +

theme_classic() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 500) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 250) +

facet_wrap(~sample)

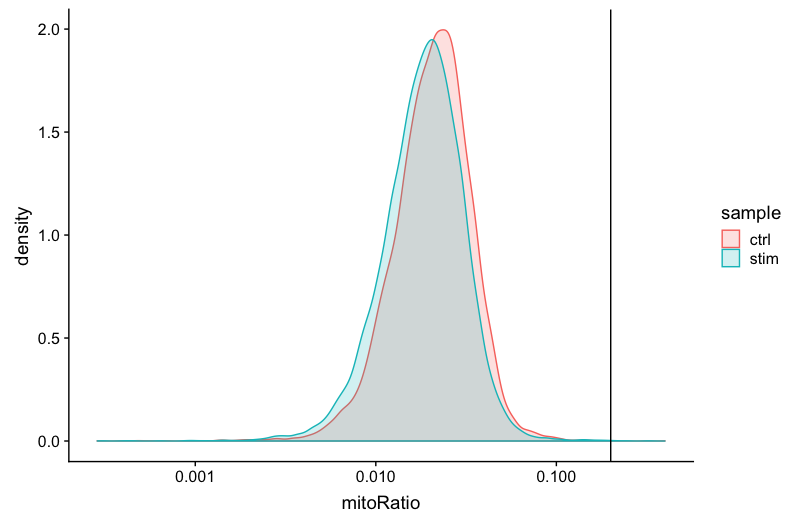

Mitochondrial counts ratio

This metric can identify whether there is a large amount of mitochondrial contamination from dead or dying cells. We define poor quality samples for mitochondrial counts as cells which surpass the 0.2 mitochondrial ratio mark, unless of course you are expecting this in your sample.

# Visualize the distribution of mitochondrial gene expression detected per cell

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(color=sample, x=mitoRatio, fill=sample)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2) +

scale_x_log10() +

theme_classic() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0.2)

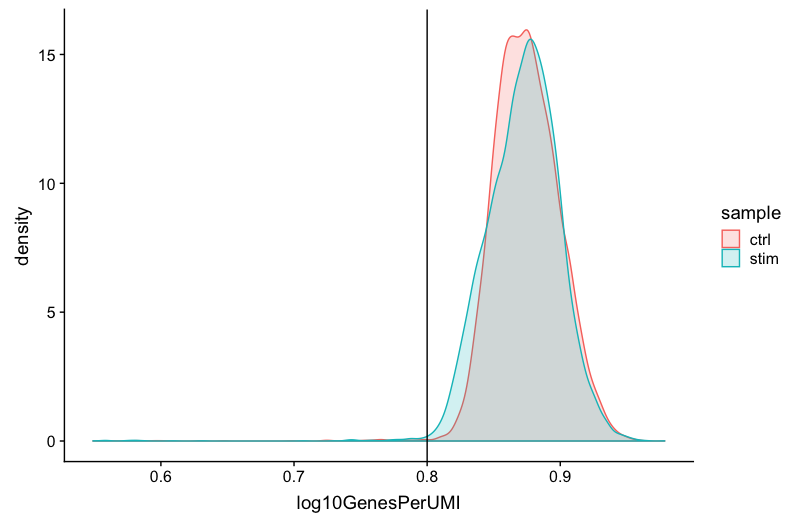

Complexity

We can see the samples where we sequenced each cell less have a higher overall complexity, that is because we have not started saturating the sequencing for any given gene for these samples. Outlier cells in these samples might be cells that have a less complex RNA species than other cells. Sometimes we can detect contamination with low complexity cell types like red blood cells via this metric. Generally, we expect the novelty score to be above 0.80.

# Visualize the overall complexity of the gene expression by visualizing the genes detected per UMI

metadata %>%

ggplot(aes(x=log10GenesPerUMI, color = sample, fill=sample)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2) +

theme_classic() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0.8)

NOTE: Reads per cell is another metric that can be useful to explore; however, the workflow used would need to save this information to assess. Generally, with this metric you hope to see all of the samples with peaks in relatively the same location between 10,000 and 100,000 reads per cell.

Filtering

In conclusion, considering any of these QC metrics in isolation can lead to misinterpretation of cellular signals. For example, cells with a comparatively high fraction of mitochondrial counts may be involved in respiratory processes and may be cells that you would like to keep. Likewise, other metrics can have other biological interpretations. Thus, always consider the joint effects of these metrics when setting thresholds and set them to be as permissive as possible to avoid filtering out viable cell populations unintentionally.

Cell-level filtering

Now that we have visualized the various metrics, we can decide on the thresholds to apply which will result in the removal of low quality cells. Often the recommendations mentioned earlier are a rough guideline, and the specific experiment needs to inform the exact thresholds chosen. We will use the following thresholds:

- nUMI > 500

- nGene > 250

- log10GenesPerUMI > 0.8

- mitoRatio < 0.2

To filter, we wil go back to our Seurat object and use the subset() function:

# Filter out low quality reads using selected thresholds - these will change with experiment

filtered_seurat <- subset(x = merged_seurat,

subset= (nUMI >= 500) &

(nGene >= 250) &

(log10GenesPerUMI > 0.80) &

(mitoRatio < 0.20))

Gene-level filtering

Within our data we will have many genes with zero counts. These genes can dramatically reduce the average expression for a cell and so we will remove them from our data. First we will remove genes that have zero expression in all cells. Additionally, we will perform some filtering by prevalence. If a gene is only expressed in a handful of cells, it is not particularly meaningful as it still brings down the averages for all other cells it is not expressed in. For our data we choose to keep only genes which are expressed in 10 or more cells.

# Output a logical vector for every gene on whether the more than zero counts per cell

# Extract counts

counts <- GetAssayData(object = filtered_seurat, slot = "counts")

# Output a logical vector for every gene on whether the more than zero counts per cell

nonzero <- counts > 0

# Sums all TRUE values and returns TRUE if more than 10 TRUE values per gene

keep_genes <- Matrix::rowSums(nonzero) >= 10

# Only keeping those genes expressed in more than 10 cells

filtered_counts <- counts[keep_genes, ]

# Reassign to filtered Seurat object

filtered_seurat <- CreateSeuratObject(filtered_counts, meta.data = filtered_seurat@meta.data)

Re-assess QC metrics

After performing the filtering, it’s recommended to look back over the metrics to make sure that your data matches your expectations and is good for downstream analysis.

-

Extract the new metadata from the filtered Seurat object to go through the same plots as with the unfiltered data

# Save filtered subset to new metadata metadata_clean <- filtered_seurat@meta.data -

Perform all of the same plots as with the unfiltered data and determine whether the thresholds used were appropriate.

Saving filtered cells

Based on these QC metrics we would identify any failed samples and move forward with our filtered cells. Often we iterate through the QC metrics using different filtering criteria; it is not necessarily a linear process. When satisfied with the filtering criteria, we would save our filtered cell object for clustering and marker identification.

# Create .RData object to load at any time

save(filtered_seurat, file="data/seurat_filtered.RData")

NOTE: We have additional materials available for exploring the metrics of a poor quality sample.

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.