Learning Objectives:

- Distinguish between variables and positional parameters

- Recognize variables and positional parameters in code written by someone else

- Implement positional parameters and variables in a bash script

- Integrate

forloops and positional parameters

What is a variable again?

As a reminder from the previous lesson, a variable is a character string to which we assign a value. The value assigned could be a number, text, filename, device, or any other type of data. It is easy to identify a variable in any bash script as they will always have the $ in front of them. Here is our very cleverly named variable: $variable

Positional parameters are a special kind of variable

“A positional parameter is an argument specified on the command line, used to launch the current process in a shell. Positional parameter values are stored in a special set of variables maintained by the shell.” (Source)

So rather than a variable that is identified inside the bash script, a positional parameter is given when you run your script. This makes it more flexible as it can be changed without modifying the script itself.

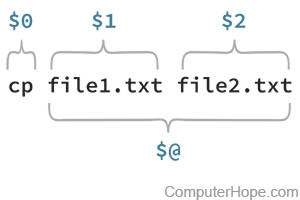

Here we can see that our command is the first positional parameter ($0) and that each of the strings afterwards are additional positional parameters (here $1 and $2). Generally when we refer to positional parameters we ignore $0 and start with $1.

It is crucial to note that different positional parameters are separated by whitespace and can be strings of any length. This means that:

$ sh myscript.sh OneTwoThree

has only given one positional parameter $1=OneTwoThree

and

$ sh myscript.sh O N E

has given three positional parameters $1=O $2=N $3=E

You can code your script to take as many positional parameters as you like but for any parameters greater than 9 you need to use curly brackets. So positional parameter 9 is $9 but positional parameter 10 is ${10}.

Finally, the variable $@ contains the value of all positional parameters except $0.

A simple example

Let’s make a script ourselves to see positional parameters in action.

From your command line type nano compliment.sh

Now copy and paste the following into your file

#!/bin/bash

echo $1 'is amazing at' $2

then exit nano, saving your script.

You may have already guessed that our script takes two different positional parameters. The first one is your first name and the second is something you are good at. Here is an example:

sh compliment.sh OliviaC acting

This will print

OliviaC is amazing at acting

You may have already guessed that we am talking about award winning actress Olivia Coleman here. But if we typed

sh compliment.sh Olivia Coleman acting

we would get

Olivia is amazing at Coleman

Technically we have just given three positional parameters $1=Olivia $2=Colman $3=acting

However, since our script does not contain $3 this is ignored.

In order to give Olivia her full due we would need to type

sh compliment.sh "Olivia Coleman" acting

The quotes tell bash that “Olivia Coleman” is a single string, $1. Both double quotes (“) and single quotes (‘) will work. Olivia has enough accolades though, so go ahead and run the script with your name (just first or both first and last) and something you are good at!

Naming positional parameters

Our previous script was so short that it was easy to remember that $1 represents a name and $2 represents a skill. However, most scripts are much longer and may contain more positional parameters. To make it easier on yourself it is often a good idea to name your positional parameters. Here is the same script we just used but with named variables.

#!/bin/bash

name=$1

skill=$2

echo $name 'is amazing at' $skill

Just like when we assigned values to variables in the last lesson, it is critical that there is no space in our assignment statements, name = $1 would not work. As we saw in the previous lesson we can also assign new variables in this manner whether or not they are coming from positional parameters. Here is the same script with the variables defined within it.

#!/bin/bash

name="Olivia Coleman"

skill="acting"

echo $name 'is amazing at' $skill

Note that defining variables within the script can make the script less flexible. If we want to change our sentence, we now need to edit our script directly rather than launching the same script but with different positional parameters.

Positional parameters and for loops

Now that we understand the basics of variables and positional parameters how can we make them work for us? We can use them in a shell script!

Lets say that we want to adapt the script we wrote in the last lesson to look for our bad read sequence in any file, and not just all the files in a whole directory. How might we do that?

Here is that same script, but we have made a few changes below:

- Remove the

forloop structure (removefor,do, anddone) - Add a couple of comments to note the script USAGE, including what the script takes in, and what the script puts out, as well as an EXAMPLE of how to run the script. It is best practice to include these types of comments. They make your life easier down the road if you ever come back to your scripts after a long time away.

- Add a line to read in a positional parameter

- Add

.paramto the output filename to make it easier to distinguish between output from this script and output from the previous script

Open up a new file using nano called generate_bad_reads_summary_param.sh. In it you can copy/paste the modified script provided here:

#!/bin/bash

## USAGE: User provides path to file that needs to checked for bad reads.

## Script will output files in the same directory

## EXAMPLE: generate_bad_reads_summary_param.sh filename

# read positional parameter

filename=$1

# create a prefix for all output files

base=$(basename $filename .subset.fq)

# tell us what file we're working on

echo $filename

# grab all the bad read records

grep -B1 -A2 NNNNNNNNNN $filename > ${base}.param.fastq

# grab the number of bad reads and write it to a summary file

grep -cH NNNNNNNNNN $filename > ${base}.param.count.summary

Save the script and exit nano. Let’s test it out with a file!

sh generate_bad_reads_summary_param.sh Irrel_kd_1.subset.fq

To see the output, you can use ls. You should see the two output files with .param. in the names.

Exercise

Say we are interested in searching for other sequences in our fastq files besides NNNNNNNNNN, and want to create output files that reflect those sequence names. But we don’t want to have to edit the script every time we have a new sequence to look for. How might we edit generate_bad_reads_summary_param.sh using positional parameters so we can feed it any sequence we want?

- Add a line to capture

sequenceas a 2nd positional parameter, and another line to echo the sequence to the user

Click here for answer

- Change what sequence we are searching for in the

grepstatements

Click here for answer

- Change the ouptput file names to include the sequence being searched

Click here for answer

- Update the

USAGEandEXAMPLEto reflect the changes you made

Click here for answer

Click here for final script

Tying everything together: Using positional parameters in a loop

The script above works great if we just have one file we want to run it on, but what if we want to run it on a large number of files? That could be tedious to run this script many times over. We could use our original looping script from the previous lesson, but if we reuse that on a new project, we will have to edit parts of the script which tell us what folder to go to before starting our for loop. It turns out that we can combine positional parameters and loops to make an even more versatile script which we wouldn’t have to edit at all between projects.

Here is example syntax of a for loop that can be used inside of a shell script to iterate through any number of positional parameters that we send to the script:

for variable_name

do

(command $variable_name)

done

This looks really similar to the for loop in the previous lesson, but it’s missing the list that the for loop normally iterates over. Why is that? When bash sees a loop like this in a script, it assumes that it is iterating over a list of user-provided positional parameters. In fact, this notation is actually shorthand for a more longform version of this for loop syntax. You may recognize "$@" from earlier in the lesson as the variable that stores all positional parameters (except $0):

for variable_name in "$@"

do

(command $variable_name)

done

In this longform syntax, "$@" means the list of all of the positional parameters that you submit to the script.

Knowing that this loop works with positional parameters, we can modify our bad reads script to take a list of files as positional parameters. Below is our bad reads looping script from the previous lesson, but we have made the following changes:

- Remove the change directory (

cd) command - Remove

in *.fqfrom theforloop - Add

.param.loopto the output filename to make it easier to distinguish between output from this script and output from the other scripts - Add USAGE and EXAMPLE comments

#!/bin/bash

## USAGE: User provides list of files that need to checked for bad reads

## Script will output files in the same directory

## EXAMPLE: generate_bad_reads_summary_param.sh *.fq

# count bad reads for each FASTQ file in the provided list of files

for filename

do

# create a prefix for all output files

base=$(basename $filename .subset.fq)

# tell us what file we're working on

echo $filename

# grab all the bad read records

grep -B1 -A2 NNNNNNNNNN $filename > ${base}.param.loop.fastq

# grab the number of bad reads and write it to a summary file

grep -cH NNNNNNNNNN $filename > ${base}.param.loop.count.summary

done

Open nano and copy the above code into a new bash script and save it as generate_bad_reads_summary_param_loop.sh

Try running the script while providing some file names:

sh generate_bad_reads_summary_param_loop.sh Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq Mov10_oe_2.subset.fq Mov10_oe_3.subset.fq

Check your outupt. By adding -t to our ls command, we can list the files in order of when they were created. The newest files will be at the top:

ls -lt

If it worked, you should now have yet another set of output files with param.loop in the file names.

Exercise

- How would you run

generate_bad_reads_summary_param_loop.shon all fastq files in a directory? ***

And that’s it! You are now very well equipped to use loops and positional parameters in the same script!

What if we still wanted to run this on multiple files AND also provide a different sequence besides “NNNNNNNNNN?” We have an advanced use lesson for positional parameters you can check out, here

Otherwise, you are all set to go on to the next lesson

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.