- Recognize the need for data management.

- Plan a good genomics experiment and getting started with project organization.

- Explain the RNA-seq experiment and its objectives.

- Define “metadata” and describe it for the example experiment.

Data Management

Project organization is one of the most important parts of a sequencing project, but is often overlooked in the excitement to get a first look at new data. While it’s best to get yourself organized before you begin analysis, it’s never too late to start.

Importantly, the methods and approaches needed for bioinformatics are the same required in a wet lab environment. Planning, documentation, and organization are essential to good, reproducible science.

Today we will breifly talk about each of these concepts. If you are interested in Research Data Management (RDM), the HMS Data Management Working Group has a website with more information, resources and contacts.

Planning

You should approach your sequencing project in a very similar way to how you do a biological experiment, and ideally, begins with experimental design. We’re going to assume that you’ve already designed a beautiful sequencing experiment to address your biological question, collected appropriate samples, and that you have enough statistical power.

During this stage it is important to keep track of how the experiment was performed and clearly tracking the source of starting materials and kits used. It is also best practice to include information about any small variations within the experiment or variation relative to standard experiments.

Organization

Every computational analysis you do is going to spawn many files, and inevitability you’ll want to run some of those analyses again. For each experiment you work on and analyze data for, it is considered best practice to get organized by creating a planned storage space (directory structure).

We will start by creating a directory that we can use for the rest of the RNA-seq session.

First, make sure that you are in your home directory.

$ cd

$ pwd

This should return /home/username.

Now make a directory for the RNA-seq analysis within the unix_lesson/ folder using the mkdir command. You can use the parents flag (-p or --parents) to complete the file path by creating any parent directories that do not exist. However, this isn’t the case here, since we already have the unix_lesson/, but it can be very useful when scripting workflows.

$ mkdir -p ~/unix_lesson/rnaseq

Next, we will set up the following structure within your project directory to keep files organized.

rnaseq

├── logs

├── meta

├── raw_data

├── reference_data

├── results

└── scripts

This is a generic structure and can be tweaked based on personal preference and analysis workflow.

logs: to keep track of the commands run and the specific parameters used, but also to have a record of any standard output that is generated while running the command.meta: for any information that describes the samples you are using, which we refer to as metadata.raw_data: for any unmodified (raw) data obtained prior to computational analysis here, e.g. FASTQ files from the sequencing center. We strongly recommend leaving this directory unmodified through the analysis.reference_data: for known information related to the reference genome that will be used in the analysis, e.g. genome sequence (FASTA), gene annotation file (GTF) associated with the genome.results: for output from the different tools you implement in your workflow. Create sub-folders specific to each tool/step of the workflow within this folder.scripts: for scripts that you write and use to run analyses/workflow.

Create subdirectories for the project by changing into rnaseq/ and then using mkdir.

$ cd ~/unix_lesson/rnaseq

$ mkdir -p logs meta raw_data reference_data results scripts

Verify that the subdirectories now exist.

ls -l

Let’s populate the rnaseq/ project with our example RNA-seq FASTQ data.

The FASTQ files are located inside ~/unix_lesson/raw_fastq/, and we need to copy them to raw_data/. We can match them by file extension with *.fq.

$ cp ~/unix_lesson/raw_fastq/*.fq raw_data/

Later in the workflow when we perform alignment, we will require genome reference files (.fa, .gtf) for alignment and read counting. These files are also in the unix_lesson/ directory inside reference_data/, we can copy over the whole folder in this case. You can use . as a shortcut for the current working directory as the destination.

$ cp -r ~/unix_lesson/reference_data/ .

Perfect, now the structure of rnaseq/ should look like this:

rnaseq

├── logs

├── meta

├── raw_data

│ ├── Irrel_kd_1.subset.fq

│ ├── Irrel_kd_2.subset.fq

│ ├── Irrel_kd_3.subset.fq

│ ├── Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

│ ├── Mov10_oe_2.subset.fq

│ └── Mov10_oe_3.subset.fq

├── reference_data

│ ├── chr1.fa

│ └── chr1-hg19_genes.gtf

├── results

└── scripts

Documentation

Documentation doesn’t stop at the sequencer! Continue to maintain a lab notebook equivalent during the analysis to make your analysis reproducible and efficient.

Log files

In your lab notebook, you likely keep track of the different reagents and kits used for a specific protocol. Similarly, recording information about the tools and parameters is important for documenting your computational experiments.

- Keep track of software versions

- Record information on parameters used and summary statistics at every step (e.g., how many adapters were removed, how many reads did not align)

- Save log files and console output

- Different tools have different ways of reporting log messages and you might have to experiment a bit to figure out what output to capture. You can redirect standard output with the

>symbol which is equivalent to1> (standard out); other tools might require you to use2>to re-direct thestandard errorinstead.

- Different tools have different ways of reporting log messages and you might have to experiment a bit to figure out what output to capture. You can redirect standard output with the

README files

After setting up the directory structure and when the analysis is running it is useful to have a README file within your project directory. This file will usually contain a quick one line summary about the project and any other lines that follow will describe the files/directories found within it. An example README is shown below. Within each sub-directory you can also include README files to describe the analysis and the files that were generated.

Keeping notes on what happened in what order, and what was done, is essential for reproducible research. If you don’t keep good notes, then you will forget what you did pretty quickly, and if you don’t know what you did, no one else has a chance.

## README ##

## This directory contains data generated during the Intro to RNA-seq course

## Date: August 23rd, 2017

There are six subdirectories in this directory:

raw_data : contains raw data

meta: contains...

logs:

reference_data:

results:

scripts:

File naming conventions

Another aspect of staying organized is making sure that all the filenames in an analysis are as consistent as possible, and are not things like alignment1.bam, but more like 20170823_kd_rep1_STAR-1.4.bam. This link and this slideshow have some good guidelines for file naming dos and don’ts.

Homework exercise

- Take a moment to create a README for the

rnaseq/folder (hint: usenanoto create the file). Give a short description of the project and brief descriptions of the types of files you will be storing within each of the sub-directories. ***

The example dataset

The dataset we are using is part of a larger study described in Kenny PJ et al., Cell Rep 2014. The authors are investigating interactions between various genes involved in Fragile X syndrome, a disease of aberrant protein production, which results in cognitive impairment and autistic-like features. The authors sought to show that RNA helicase MOV10 regulates the translation of RNAs involved in Fragile X syndrome.

From this study we are using the RNA-seq data which is publicly available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA). In addition to the raw sequence data we also need to collect information about the data, also known as metadata. We are usually quick to want to begin analysis of the sequence data (FASTQ files), but how useful is it if we know nothing about the samples that this sequence data originated from? Some relevant metadata for our dataset is provided below:

- The RNA was extracted from HEK293F cells that were transfected with a MOV10 transgene, MOV10 siRNA, or an irrelevant siRNA. (For this workshop we won’t be using the MOV10 knock down samples.)

- The libraries for this dataset are stranded and were generated using the standard Tru-seq prep kit (using the dUTP method).

- Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq-2500 and 100bp single end reads were generated.

- The full dataset was sequenced to ~40 million reads per sample, but for this workshop we will be looking at a small subset on chr1 (~300,000 reads/sample).

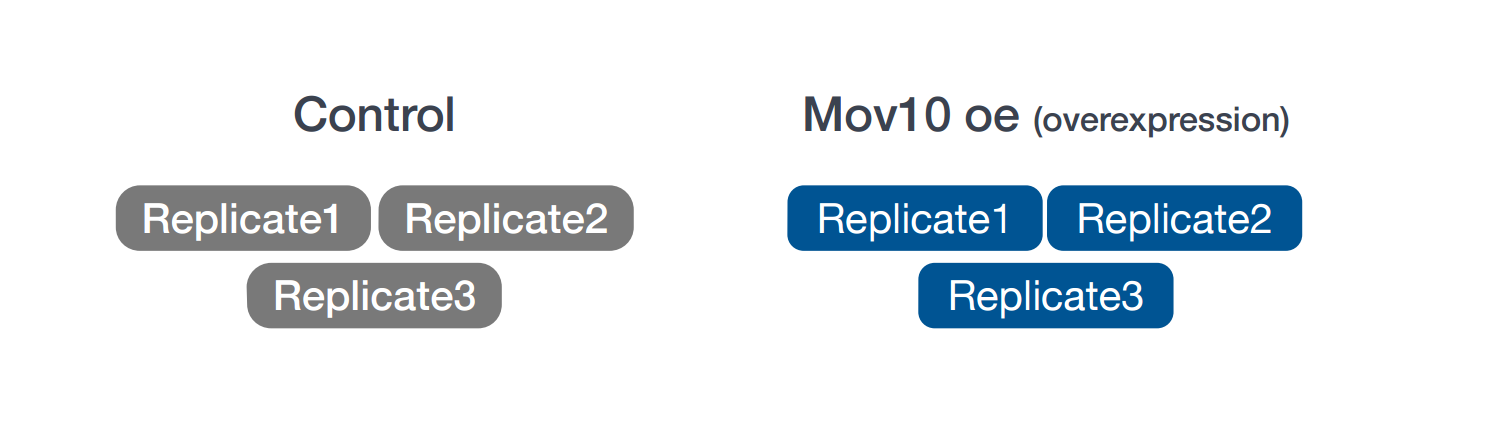

- For each group we have three replicates as described in the figure below.

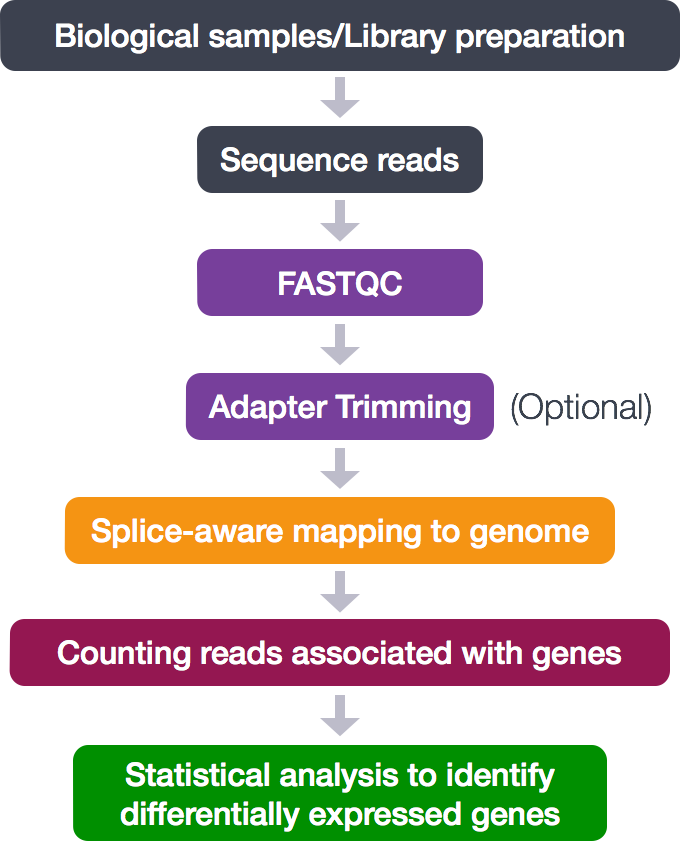

The RNA-seq workflow

For any bioinformatics experiment you will have to go through a series of steps in order to obtain your final desired output. The execution of these steps in a sequential manner is what we often refer to as a workflow or pipeline. A simplified version of the workflow we will be using in this course is provided below. We have some of the steps briefly outlined here, but we will be covering some of these (#2, #4 and #5) in more detail during this workshop.

- Library preparation of biological samples (pre-sequencing)

- Quality control - Assessing quality of sequence reads using FastQC

- Quality control (Optional) - Adapter Trimming

- Align reads to reference genome using STAR (splice-aware aligner)

- Quantifying expression/Counting the number of reads mapping to each gene

- Statistical analysis to identify differentially expressed genes (count normalization, linear modeling using R-based tools)

These workflows in bioinformatics adopt a plug-and-play approach in that the output of one tool can be easily used as input to another tool without any extensive configuration. Having standards for data formats is what makes this feasible. Standards ensure that data is stored in a way that is generally accepted and agreed upon within the community. The tools that are used to analyze data at different stages of the workflow are therefore built under the assumption that the data will be provided in a specific format.

Best practices for NGS Analysis

Ok so now you are all set up and have begun your analysis. You have followed best practices to set up your analysis directory structure in a way such that someone unfamiliar with your project should be able to look at it and understand what you did and why. But there is more…:

-

Make sure to use the appropriate software. Do your research and find out what is best for the data you are working with. Don’t just work with tools that you are able to easily install. Also, make sure you are using the most up-to-date versions! If you run out-of-date software, you are probably introducing errors into your workflow; and you may be missing out on more accurate methods.

-

Keep up with the literature. Bioinformatics is a fast-moving field and it’s always good to stay in the know about recent developments. This will help you determine what is appropriate and what is not.

-

Do not re-invent the wheel. If you run into problems, more often than not someone has already encountered that same problem. A solution is either already available or someone is working on it – so find it! Ask colleagues or search/ask online forums such as BioStars.

-

Testing is essential. If you are using a tool for the first time, test it out on a single sample or a subset of the data before running your entire dataset through. This will allow you to debug quicker and give you a chance to also get a feel for the tool and the different parameters.

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

- The materials used in this lesson were derived from work that is Copyright © Data Carpentry (http://datacarpentry.org/). All Data Carpentry instructional material is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0).

- Adapted from the lesson by Tracy Teal. Original contributors: Paul Wilson, Milad Fatenejad, Sasha Wood and Radhika Khetani for Software Carpentry (http://software-carpentry.org/)