Learning Objectives

- How do you access the shell?

- How do you use it?

- Getting around the Unix file system

- looking at files

- manipulating files

- automating tasks

- What is it good for?

Setting up

We will spend most of our time learning about the basics of the shell by exploring experimental data.

Since we are going to be working with this data on our remote cluster, O2, we first need to log in. After we’re logged on, we will each make our own copy of the example data folder.

Logging in

With Macs

Macs have a utility application called “Terminal” for performing tasks on the command line (shell), both locally and on remote machines. We will be using it to log into O2.

With Windows

By default, there is no terminal for the bash shell available in the Windows OS, so you have to use a downloaded program, “Git BASH”. Git BASH is part of the Git for Windows download, and is a shell (bash) emulator.

You can also use Putty to log in to remote machines from Windows computers, but it is a little more involved and has different capabilities.

Let’s log in!

Type in the following command with your username to login:

ssh username@o2.hms.harvard.edu

You will receive a prompt for your password, and you should type in your associated password; note that the cursor will not move as you type in your password.

A warning might pop up the first time you try to connect to a remote machine, type “Yes” or “Y”.

Copying example data folder

Once logged in, you should see the O2 icon, some news, and the command prompt:

[rc_training10@login01 ~]$

The command prompt will have some characters before it, something like [rc_training01@login01 ~], this is telling you what the name of the computer you are working on is.

The first command we will type on the command prompt will be to start a so-called “interactive session” on O2.

$ srun --pty -p interactive -t 0-12:00 --mem 1G --reservation=HBC /bin/bash

Press enter after you type in that command. You will get a couple of messages, but in a few seconds you should get back the command prompt $; the string of characters before the command prompt, however, have changed. They should say something like [rc_training01@compute-a-16-73 ~]. We will be explaining what this means in more detail later when we talk about HPC and O2.

Make sure that your command prompt is now preceded by a character string that contains the word “compute”.

NOTE: When you run the

sruncommand after this workshop with your own account please use the following command (without the--reservationoption):

srun --pty -p interactive -t 0-12:00 --mem 1G /bin/bashThe “reservation” is only active for the training accounts, and only for the duration of this workshop.

Copy our example data folder to your home directory using the following command:

$ cp -r /n/groups/hbctraining/unix_lesson/ .

‘cp’ is the command for copy. This command required you to specify the location of the item you want to copy (/groups/hbctraining/unix_lesson/) and the location of the destination (.); please note the space between the 2 in the command. The “-r” is an option that modifies the copy command to do something slightly different than usual. The “.” means “here”, i.e. the destination location is where you currently are.

Starting with the shell

We have each created our own copy of the example data folder into our home directory, unix_lesson. Let’s go into the data folder and explore the data using the shell.

$ cd unix_lesson

‘cd’ stands for ‘change directory’

Let’s see what is in here. Type:

$ ls

You will see:

genomics_data other raw_fastq README.txt reference_data

ls stands for ‘list’ and it lists the contents of a directory.

There are five items listed. What types of files are they? We can use a “modifier” with ls to get more information; this modifier is called an argument (more below).

$ ls -F

genomics_data/ other/ raw_fastq/ README.txt reference_data/

Anything with a “/” after it is a directory. Things with a “*” after them are programs. If there are no decorations after the name, it’s a file.

All commands are essentially programs that are able to perform specific, commonly-used tasks.

You can also use the command:

$ ls -l

to see whether items in a directory are files or directories. ls -l gives a lot more information too.

total 124

drwxrwsr-x 2 mp298 mp298 78 Sep 30 10:47 genomics_data

drwxrwsr-x 6 mp298 mp298 107 Sep 30 10:47 other

drwxrwsr-x 2 mp298 mp298 228 Sep 30 10:47 raw_fastq

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mp298 mp298 377 Sep 30 10:47 README.txt

drwxrwsr-x 2 mp298 mp298 238 Sep 30 10:47 reference_data

Let’s go into the raw_fastq directory and see what is in there.

$ cd raw_fastq/

$ ls -F

Irrel_kd_1.subset.fq Irrel_kd_3.subset.fq Mov10_oe_2.subset.fq

Irrel_kd_2.subset.fq Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq Mov10_oe_3.subset.fq

All six items in this directory have no trailing slashes, so they are all files, not folders or programs.

Arguments

Most commands take additional arguments that control their exact behavior. For example, -F and -l are arguments to ls. The ls command, like many commands, take a lot of arguments. Another useful one is -a, which shows everything, including hidden files. How do we know what the available arguments that go with a particular command are?

Most commonly used shell commands have a manual available in the shell. You can access the

manual using the man command. Try entering:

$ man ls

This will open the manual page for ls. Use the ‘space’ key to go forward and ‘b’ to go backwards. When you are done reading, just hit q to quit.

Commands that are run from the shell can get extremely complicated. To see an example, open up the manual page for the find command. No one can possibly learn all of these arguments, of course. So you will probably find yourself referring to the manual page frequently.

If the manual page within the terminal is hard to read and traverse, the manual exists online, use your web searching powers to get it! In addition to the arguments, you can also find good examples online; Google is your friend.

The Unix directory file structure (a.k.a. where am I?)

As you’ve already just seen, you can move around in different directories or folders at the command line. Why would you want to do this, rather than just navigating around the normal way using a GUI (GUI = Graphical User Interface, pronounced like “gooey”).

Moving around the file system

Let’s practice moving around a bit.

We’re going to work in that unix_lesson directory.

First we did something like go to the folder of our username. Then we opened unix_lesson then raw_fastq

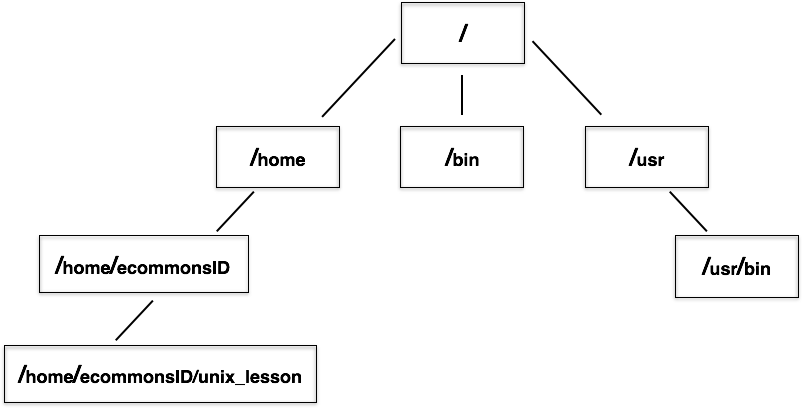

Like on any computer you have used before the file structure within unix is hierarchical, like an upside down tree with root (/) as the starting point of the tree-like structure:

That root (/) is often also called the ‘top’ level.

When you log in to a remote computer you are on one of the branches of that tree, your home directory (e.g. /home/username)

On mac OS, which is a UNIX-based OS, the root level is also “/”. On a windows OS, it is drive specific; generally “C:" is considered root, but it changes to “D:/”, if you are on that drive.

Now let’s go do that same navigation at the command line.

Type:

$ cd

This puts you in your home directory. No matter where you are in the directory system,

cdwill always bring you back to your home directory.

Now using cd and ls, go in to the unix_lesson directory and list its contents. Now go into the raw_fastq directory, and list its contents.

Let’s also check to see where we are. Sometimes when we’re wandering around in the file system, it’s easy to lose track of where we are. The command that tells you this is:

$ pwd

This stands for ‘print working directory’. i.e. the directory you’re currently working in.

What if we want to move back up and out of the raw_fastq directory? Can we just type cd unix_lesson? Try it and see what happens.

To go ‘back up a level’ we can use ..

Type:

$ cd ..

Now do ls and pwd.

..denotes parent directory, and you can use it anywhere in the system to go back to the parent directory. Can you think of an example when this won’t work?

Finally, there is handy command that can help you see the structure of any directory, namely tree.

#Ensure that you are in your unix_lesson directory and run the following command

$ tree

Examining the contents of other directories

By default, the ls commands lists the contents of the working directory (i.e. the directory you are in). You can always find the directory you are in using the pwd command. However, you can also give ls the names of other directories to view. Navigate to the home directory if you are not already there.

Type:

$ cd

Then enter the command:

$ ls unix_lesson/

This will list the contents of the unix_lesson directory without you having to navigate there.

The cd command works in a similar way.

$ cd unix_lesson/raw_fastq/

$ pwd

You should now be in raw_fastq and you got there without having to go through the intermediate directory.

If you are aware of the directory structure, you can string together as long a list as you like.

Exercise

List the Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq file from your home directory without changing directories

Full vs. Relative Paths

The cd command takes an argument which is the directory name. Directories can be specified using either a relative path or a full path. As we know, the directories on the computer are arranged into a hierarchy. The full path tells you where a directory is in that hierarchy. Navigate to the home directory (cd). Now, enter the pwd command and you should see:

$ pwd

/home/username

which is the full path for your home directory. This tells you that you are in a directory called username, which sits inside a directory called home which sits inside the very top directory in the hierarchy, the root directory. So, to summarize: username is a directory in home which is a directory in /.

Now enter the following command:

$ cd /home/username/unix_lesson/raw_fastq/

This jumps to raw_fastq. Now go back to the home directory (cd). We saw

earlier that the command:

$ cd unix_lesson/raw_fastq/

had the same effect - it took us to the raw_fastq directory. But, instead of specifying the full path (/home/username/unix_lesson/raw_fastq), we specified a relative path. In other words, we specified the path relative to our current working directory.

A full path always starts with a /, a relative path does not.

A relative path is like getting directions from someone on the street. They tell you to “go right at the Stop sign, and then turn left on Main Street”. That works great if you’re standing there together, but not so well if you’re trying to tell someone how to get there from another country. A full path is like GPS coordinates. It tells you exactly where something is no matter where you are right now.

You can usually use either a full path or a relative path depending on what is most convenient. If we are in the home directory, it is more convenient to just enter the relative path since it involves less typing.

Over time, it will become easier for you to keep a mental note of the structure of the directories that you are using and how to quickly navigate among them.

Exercise

Change directories to /home/username/unix_lesson/raw_fastq/, and list the contents of unix_lesson/other without changing directories again.

Saving time with tab completion, wildcards and other shortcuts

Tab completion

Navigate to the home directory. Typing out directory names can waste a lot of time. When you start typing out the name of a directory, then hit the tab key, the shell will try to fill in the rest of the directory name. For example, type cd to get back to your home directly, then enter:

$ cd uni<tab>

The shell will fill in the rest of the directory name for unix_lesson. Now go to unix_lesson/raw_fastq and

$ ls Mov10_oe_<tab><tab>

When you hit the first tab, nothing happens. The reason is that there are multiple directories in the home directory which start with Mov10_oe_. Thus, the shell does not know which one to fill in. When you hit tab again, the shell will list the possible choices.

Tab completion can also fill in the names of commands. For example, enter e<tab><tab>. You will see the name of every command that starts with an e. One of those is echo. If you enter ech<tab> you will see that tab completion works.

Tab completion is your friend! It helps prevent spelling mistakes, and speeds up the process of typing in the full command.

Wild cards

Navigate to the ~/unix_lesson/raw_fastq directory. This directory contains FASTQ files from a next-generation sequencing dataset.

The ‘*’ character is a shortcut for “everything”. Thus, if you enter ls *, you will see all of the contents of a given directory. Now try this command:

$ ls *fq

This lists every file that ends with a fq. This command:

$ ls /usr/bin/*.sh

Lists every file in /usr/bin that ends in the characters .sh.

$ ls Mov10*fq

lists only the files that begin with ‘Mov10’ and end with ‘fq’

So how does this actually work? The shell (bash) considers an asterisk “*” to be a wildcard character that can be used to substitute for any other single character or a string of characters.

An asterisk/star is only one of the many wildcards in UNIX, but this is the most powerful one and we will be using this one the most for our exercises.

Exercise

Do each of the following using a single ls command without

navigating to a different directory.

- List all of the files in

/binthat start with the letter ‘c’ - List all of the files in

/binthat contain the letter ‘a’ - List all of the files in

/binthat end with the letter ‘o’

BONUS: List all of the files in /bin that contain the letter ‘a’ or ‘c’.

Shortcuts

There are some shortcuts which you should know about. Dealing with the

home directory is very common. So, in the shell the tilde character,

“~”, is a shortcut for your home directory. Navigate to the raw_fastq

directory:

$ cd

$ cd unix_lesson/raw_fastq

Then enter the command:

$ ls ~

This prints the contents of your home directory, without you having to type the full path because the tilde “~” is equivalent to “/home/username”.

Another shortcut is the “..”:

$ ls ..

The shortcut .. always refers to the directory above your current directory. So, it prints the contents of the unix_lesson. You can chain these together, so:

$ ls ../..

prints the contents of /home/username which is your home directory.

Finally, the special directory . always refers to your current directory. So, ls, ls ., and ls ././././. all do the same thing, they print the contents of the current directory. This may seem like a useless shortcut right now, but we used it earlier when we copied over the data to our home directory.

To summarize, while you are in your home directory, the commands ls ~, ls ~/., and ls /home/username all do exactly the same thing. These shortcuts are not necessary, but they are really convenient!

Command History

You can easily access previous commands. Hit the up arrow. Hit it again. You can step backwards through your command history. The down arrow takes your forwards in the command history.

‘Ctrl-r’ will do a reverse-search through your command history. This is very useful.

You can also review your recent commands with the history command. Just enter:

$ history

to see a numbered list of recent commands, including this just issues

history command. Only a certain number of commands are stored and displayed with history, there is a way to modify this to store a different number.

NOTE: So far we have only run very short commands that have few or no arguments, and so it would be faster to just retype it than to check the history. However, as you start to run analyses on the commadn-line you will find your commands to be more complex and the history to be very useful!

Other handy command-related shortcuts

- will cancel the command you are writing, and give you a fresh prompt.

- will bring you to the start of the command you are writing.

- will bring you to the end of the command.

Examining Files

We now know how to move around the file system and look at the contents of directories, but how do we look at the contents of files?

The easiest way to examine a file is to just print out all of the

contents using the command cat. Print the contents of unix_lesson/other/sequences.fa by entering the following command:

$ cat ~/unix_lesson/other/sequences.fa

This prints out the all the contents of sequences.fa to the screen.

catstands for catenate; it has many uses and printing the contents of a files onto the terminal is one of them.

What does this file contain?

cat is a terrific command, but when the file is really big, it can be annoying to use. In practice, when you are running your analyses on the command-line you will most likely be dealing with large files. The command, less, is useful for this case. Let’s take a look at the list of raw_fastq files and add the -h modifier:

ls -lh ~/unix_lesson/raw_fastq

The

lscommand has a modifier-hwhen paired with-l, will print sizes of files in human readable format

In the fourth column you wll see the size of each of these files, and you can see they are quite large, so we probably do not want to use the cat command to look at them. Instead, we can use the less command.

Move back to our raw_fastq directory and enter the following command:

less Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

We will explore FASTQ files in more detail later, but notice that FASTQ files have four lines of data associated with every sequence read. Not only is there a header line and the nucleotide sequence, similar to a FASTA file, but FASTQ files also contain quality information for each nucleotide in the sequence.

The less command opens the file, and lets you navigate through it. The keys used to move around the file are identical to the man command.

Shortcuts for less

| key | action |

|---|---|

| SPACE | to go forward |

| b | to go backwards |

| g | to go to the beginning |

| G | to go to the end |

| q | to quit |

less also gives you a way of searching through files. Just hit the / key to begin a search. Enter the name of the string of characters you would like to search for and hit enter. It will jump to the next location where that string is found. If you hit / then ENTER, less will just repeat the previous search. less searches from the current location and works its way forward. If you are at the end of the file and search for the word “cat”, less will not find it. You need to go to the beginning of the file and search.

For instance, let’s search for the sequence GAGACCC in our file. You can see that we go right to that sequence and can see what it looks like. To exit hit q.

The man command (program) actually uses less internally and therefore uses the same keys and methods, so you can search manuals using / as well!

There’s another way that we can look at files, and in this case, just look at part of them. This can be particularly useful if we just want to see the beginning or end of the file, or see how it’s formatted.

The commands are head and tail and they just let you look at

the beginning and end of a file respectively.

$ head Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

$ tail Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

The -n option to either of these commands can be used to print the first or last n lines of a file. To print the first/last line of the file use:

$ head -n 1 Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

$ tail -n 1 Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

Creating, moving, copying, and removing

Now we can move around in the file structure, look at files, search files, redirect. But what if we want to do normal things like copy files or move them around or get rid of them. Sure we could do most of these things without the command line, but what fun would that be?! Besides it’s often faster to do it at the command line, or you’ll be on a remote server like Amazon where you won’t have another option.

Our raw data in this case is fastq files. We don’t want to change the original files, so let’s make a copy to work with.

Lets copy the file using the copy cp command. Navigate to the raw_fastq directory and enter:

$ cp Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq Mov10_oe_1.subset-copy.fq

$ ls -l

Now Mov10_oe_1.subset-copy.fq has been created as a copy of Mov10_oe_1.subset.fq

Let’s make a ‘backup’ directory where we can put this file.

The mkdir command is used to make a directory. Just enter mkdir

followed by a space, then the directory name.

$ mkdir backup

File/directory/program names with spaces in them do not work in unix, use characters like hyphens or underscores instead.

We can now move our backed up file in to this directory. We can move files around using the command mv. Enter this command:

$ mv *copy.fq backup

$ ls -l backup

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mp298 mp298 75706556 Sep 30 13:56 Mov10_oe_1.subset-copy.fq

The mv command is also how you rename files. Since this file is so

important, let’s rename it:

$ cd backup

$ mv Mov10_oe_1.subset-copy.fq Mov10_oe_1.subset-backup.fq

$ ls

Mov10_oe_1.subset-backup.fq

Finally, we decided this was silly and want to start over.

$ cd ..

$ rm backup/Mov*

The

rmfile permanently removes the file. Be careful with this command. The shell doesn’t just nicely put the files in the Trash. They’re really gone.Same with moving and renaming files. It will not ask you if you are sure that you want to “replace existing file”. You can use

rm -iif you want it to ask before deleting the file(s).

We really don’t need these backup directories, so, let’s delete both. By default, rm, will NOT delete directories, but you use the -r flag if you are sure that you want to delete the directories and everything within them. To be safe, let’s use it with the -i flag.

$ rm -ri backup/

-r: recursive, commonly used as an option when working with directories, e.g. withcp.-i: prompt before every removal.

Commands, options, and keystrokes covered

bash

cd

ls

man

pwd

~ # home dir

. # current dir

.. # parent dir

* # wildcard

echo

ctrl + c # cancel current command

ctrl + a # start of line

ctrl + e # end of line

history

cat

less

head

tail

cp

mdkir

mv

rm

Information on the shell

shell cheat sheets:

- http://fosswire.com/post/2007/08/unixlinux-command-cheat-sheet/

- https://github.com/swcarpentry/boot-camps/blob/master/shell/shell_cheatsheet.md

Explain shell - a web site where you can see what the different components of a shell command are doing.

Data Carpentry tutorial: Introduction to the Command Line for Genomics

General help:

- http://tldp.org/HOWTO/Bash-Prog-Intro-HOWTO.html

- man bash

- Google - if you don’t know how to do something, try Googling it. Other people have probably had the same question.

- Learn by doing. There’s no real other way to learn this than by trying it out. Write your next paper in vim (really emacs or vi), open pdfs from the command line, automate something you don’t really need to automate.

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

- The materials used in this lesson were derived from work that is Copyright © Data Carpentry (http://datacarpentry.org/). All Data Carpentry instructional material is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0).

- Adapted from the lesson by Tracy Teal. Original contributors: Paul Wilson, Milad Fatenejad, Sasha Wood and Radhika Khetani for Software Carpentry (http://software-carpentry.org/)