Approximate time: 75 minutes

Data Wrangling with Tidyverse

The Tidyverse suite of integrated packages are designed to work together to make common data science operations more user friendly. The packages have functions for data wrangling, tidying, reading/writing, parsing, and visualizing, among others. There is a freely available book, R for Data Science, with detailed descriptions and practical examples of the tools available and how they work together. We will explore the basic syntax for working with these packages, as well as, specific functions for data wrangling with the ‘dplyr’ package, data tidying with the ‘tidyr’ package, and data visualization with the ‘ggplot2’ package.

All of these packages use the same style of code, which is snake_case formatting for all function names and arguments. You can peruse the tidy style guide for additional information.

Adding files to your working directory

We will be bringing in a new file with results from a differential expression analysis, to work with in this lesson. Please right-click here to download it to your data folder as we did before (choose to Save Link As or Download Linked File As). You should see it in data folder in the RStudio “Files” tab.

Reading in the data files

Let’s read in this new file we just downloaded and load the tidyverse library:

res_tableOE <- read.csv(file = "data/Mov10oe_DE_results.csv", row.names = 1)

library(tidyverse)

Tidyverse basics

The Tidyverse suite of packages introduces users to a set of data structures, functions and operators to make working with data more intuitive, but is slightly different from the way we do things in base R. Two important new concepts we will focus on are pipes and tibbles.

Pipes

Stringing together commands in R can be quite daunting. Also, trying to understand code that has many nested functions can be confusing.

To make R code more human readable, the Tidyverse tools use the pipe, %>%, which was acquired from the magrittr package and is now part of the dplyr package that is installed automatically with Tidyverse. The pipe allows the output of a previous command to be used as input to another command instead of using nested functions.

NOTE: Shortcut to write the pipe is shift + command + M

An example of using the pipe to run multiple commands:

## A single command

sqrt(83)

## Base R method of running more than one command

round(sqrt(83), digits = 2)

## Running more than one command with piping

sqrt(83) %>% round(digits = 2)

The pipe represents a much easier way of writing and deciphering R code, and so we will be taking advantage of it, when possible, as we work through the remaining lesson.

Exercises

-

Extract the

replicatecolumn from themetadatadata frame (use the$notation) and save the values to a vector namedrep_number. -

Use the pipe (

%>%) to perform two steps in a single line:- Turn

rep_numberinto a factor. - Use the

head()function to return the first six values of therep_numberfactor.

- Turn

Tibbles

A core component of the tidyverse is the tibble. Tibbles are a modern rework of the standard data.frame, with some internal improvements to make code more reliable. They are data frames, but do not follow all of the same rules. For example, tibbles can have numbers/symbols for column names, which is not normally allowed in base R.

Important: tidyverse is very opininated about row names. These packages insist that all column data (e.g. data.frame) be treated equally, and that special designation of a column as rownames should be deprecated. Tibble provides simple utility functions to handle rownames: rownames_to_column() and column_to_rownames(). More help for dealing with row names in tibbles can be found:

help("rownames", "tibble")

Tibbles can be created directly using the tibble() function or data frames can be converted into tibbles using as_tibble(name_of_df).

NOTE: The function

as_tibble()will ignore row names, so if a column representing the row names is needed, then the functionrownames_to_column(name_of_df)should be run prior to turning the data.frame into a tibble. Also,as_tibble()will not coerce character vectors to factors by default.

Exercises

-

Create a tibble called

df_tibbleusing thetibble()function to combine the vectorsspeciesandglengths. NOTE: yourglengthsvector may not be the same length asspecies, so you will need to use an appropriately sized subset. -

Change the

metadatadata frame to a tibble calledmeta_tibble. Use therownames_to_column()function to preserve the rownames combined with using%>%and theas_tibble()function.

A nice feature of a tibble is that when printing a variable to screen, it will show only the first 10 rows and the columns that fit to the screen by default. This is nice since you don’t have to specify head() to take a quick look at your dataset.

# Default printing of data.frame

rpkm_data

# Default printing of tibble

rpkm_data %>%

rownames_to_column() %>%

as_tibble()

NOTE: If it is desirable to view more of the dataset, the

print()function can change the number of rows or columns displayed.# Printing of tibble with print() - change defaults rpkm_data %>% rownames_to_column() %>% as_tibble() %>% print(n = 20, width = Inf)

Tidyverse tools

While all of the tools in the Tidyverse suite are deserving of being explored in more depth, we are going to investigate only the tools we will be using most for data wrangling and tidying.

NOTE: A large number of tidyverse functions will work with both tibbles and dataframes, and the data structure of the output will be identical to the input. However, there are some functions that will return a tibble (without row names), whether or not a tibble or dataframe is provided.

Dplyr

The most useful tool in the tidyverse is dplyr. It’s a swiss-army knife for data wrangling. dplyr has many handy functions that we recommend incorporating into your analysis:

select()extracts columns and returns a tibble.arrange()changes the ordering of the rows.filter()picks cases based on their values.mutate()adds new variables that are functions of existing variables.rename()easily changes the name of a column(s)summarise()reduces multiple values down to a single summary.pull()extracts a single column as a vector._join()group of functions that merge two data frames together, includes (inner_join(),left_join(),right_join(), andfull_join()).

NOTE: dplyr underwent a massive revision in 2017, switching versions from 0.5 to 0.7. If you consult other dplyr tutorials online, note that many materials developed prior to 2017 are no longer correct. In particular, this applies to writing functions with dplyr (see Notes section below).

select()

To extract columns from a tibble we can use the select() function.

# Convert the res_tableOE data frame to a tibble

res_tableOE <- res_tableOE %>%

rownames_to_column(var="gene") %>%

as_tibble()

# extract selected columns from res_tableOE

res_tableOE %>%

select(gene, baseMean, log2FoldChange, padj)

Conversely, you can remove columns you don’t want with negative selection.

res_tableOE %>%

select(-c(lfcSE, stat, pvalue))

## # A tibble: 23,368 x 4

## gene baseMean log2FoldChange padj

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1/2-SBSRNA4 45.6520399 0.266586547 2.708964e-01

## 2 A1BG 61.0931017 0.208057615 3.638671e-01

## 3 A1BG-AS1 175.6658069 -0.051825739 7.837586e-01

## 4 A1CF 0.2376919 0.012557390 NA

## 5 A2LD1 89.6179845 0.343006364 7.652553e-02

## 6 A2M 5.8600841 -0.270449534 2.318666e-01

## 7 A2ML1 2.4240553 0.236041349 NA

## 8 A2MP1 1.3203237 0.079525469 NA

## 9 A4GALT 64.5409534 0.795049160 2.875565e-05

## 10 A4GNT 0.1912781 0.009458374 NA

## # ... with 23,358 more rows

Let’s save that tibble as a new variable called sub_res:

sub_res <- res_tableOE %>%

select(-c(lfcSE, stat, pvalue))

arrange()

Note that the rows are sorted by the gene symbol. Let’s sort them by adjusted P value instead with arrange().

arrange(sub_res, padj)

## # A tibble: 23,368 x 4

## gene baseMean log2FoldChange padj

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 MOV10 21681.7998 4.7695983 0.000000e+00

## 2 H1F0 7881.0811 1.5250811 2.007733e-162

## 3 HSPA6 168.2522 4.4993734 1.969313e-134

## 4 HIST1H1C 1741.3830 1.4868361 5.116720e-101

## 5 TXNIP 5133.7486 1.3868320 4.882246e-90

## 6 NEAT1 21973.7061 0.9087853 2.269464e-83

## 7 KLF10 1694.2109 1.2093969 9.257431e-78

## 8 INSIG1 11872.5106 1.2260848 8.853278e-70

## 9 NR1D1 969.9119 1.5236259 1.376753e-64

## 10 WDFY1 1422.7361 1.0629160 1.298076e-61

## # ... with 23,358 more rows

filter()

Let’s keep only genes that are expressed (baseMean above 0) with an adjusted P value below 0.01. You can perform multiple filter() operations together in a single command.

sub_res %>%

filter(baseMean > 0 & padj < 0.01)

## # A tibble: 4,959 x 4

## gene baseMean log2FoldChange padj

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 A4GALT 64.5 0.798 2.40e- 5

## 2 AAGAB 2614. -0.390 1.68e-11

## 3 AAMP 3157. -0.380 9.11e-13

## 4 AARS 3690. 0.167 2.10e- 3

## 5 AARS2 2255. -0.204 3.77e- 4

## 6 AASDHPPT 3561. -0.293 3.79e- 7

## 7 AASS 1018. 0.347 7.94e- 5

## 8 AATF 2613. -0.290 1.97e- 7

## 9 ABAT 384. 0.384 1.99e- 4

## 10 ABCA1 108. 0.833 4.19e- 7

## # ... with 4,949 more rows

mutate()

mutate() enables you to create a new column from an existing column. Let’s generate log10 calculations of our baseMeans for each gene.

sub_res %>%

mutate(log10BaseMean = log10(baseMean)) %>%

select(gene, baseMean, log10BaseMean)

## # A tibble: 23,368 x 3

## gene baseMean log10BaseMean

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1/2-SBSRNA4 45.7 1.66

## 2 A1BG 61.1 1.79

## 3 A1BG-AS1 176. 2.24

## 4 A1CF 0.238 -0.624

## 5 A2LD1 89.6 1.95

## 6 A2M 5.86 0.768

## 7 A2ML1 2.42 0.385

## 8 A2MP1 1.32 0.121

## 9 A4GALT 64.5 1.81

## 10 A4GNT 0.191 -0.718

## # ... with 23,358 more rows

rename()

You can quickly rename an existing column with rename(). The syntax is new_name = old_name.

sub_res %>%

rename(symbol = gene)

## # A tibble: 23,368 x 4

## symbol baseMean log2FoldChange padj

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1/2-SBSRNA4 45.7 0.268 0.264

## 2 A1BG 61.1 0.209 0.357

## 3 A1BG-AS1 176. -0.0519 0.781

## 4 A1CF 0.238 0.0130 NA

## 5 A2LD1 89.6 0.345 0.0722

## 6 A2M 5.86 -0.274 0.226

## 7 A2ML1 2.42 0.240 NA

## 8 A2MP1 1.32 0.0811 NA

## 9 A4GALT 64.5 0.798 0.0000240

## 10 A4GNT 0.191 0.00952 NA

## # ... with 23,358 more rows

pull()

In the recent dplyr 0.7 update, pull() was added as a quick way to access column data as a vector. This is very handy in chain operations with the pipe operator.

# Extract first 10 values from the gene column

pull(sub_res, gene) %>% head()

_join()

Dplyr has a powerful group of join operations, which join together a pair of data frames based on a variable or set of variables present in both data frames that uniquely identify all observations. These variables are called keys.

-

inner_join: Only the rows with keys present in both datasets will be joined together. -

left_join: Keeps all the rows from the first dataset, regardless of whether in second dataset, and joins the rows of the second that have keys in the first. -

right_join: Keeps all the rows from the second dataset, regardless of whether in first dataset, and joins the rows of the first that have keys in the second. -

full_join: Keeps all rows in both datasets. Rows without matching keys will have NA values for those variables from the other dataset.

To practice with the join functions, we can create the data detailed below.

-

Description: For a research project, we asked healthy volunteers and cancer patients questions about their diet and exercise. We also collected blood work for each individual, and each person was given a unique ID. Create the data frames

behaviorandbloodby copy/pasting the code below: -

Data:

# Creating behavior dataframe ID <- c(546, 983, 042, 952, 853, 061) diet <- c("veg", "pes", "omni", "omni", "omni", "omni") exercise <- c("high", "low", "low", "low", "med", "high") behavior <- data.frame(ID, diet, exercise) # Creating blood dataframe ID <- c(983, 952, 704, 555, 853, 061, 042, 237, 145, 581, 249, 467, 841, 546) blood_levels <- c(43543, 465, 4634, 94568, 134, 347, 2345, 5439, 850, 6840, 5483, 66452, 54371, 1347) blood <- data.frame(ID, blood_levels)

Not all individuals with blood samples have associated behavioral information. Using the _join family of functions, let’s practice the different options for joining the two data frames.

To join only the IDs present in both data frames, we could use the inner_join() function:

# Inner join

inner_join(blood, behavior)

Alternatively, if we wanted to return all blood IDs, but include only the behavior IDs that match, we could use the left_join() function:

# Left join

left_join(blood, behavior)

We could also do the same thing but return all behavior IDs and matching blood IDs using right_join():

# Right join

right_join(blood, behavior)

Finally, we could return all IDs from both data frames regardless whether there is a matching key (ID):

# Full join

full_join(blood, behavior)

NOTE: If the names in the two data frames do not have the same column names, then you would need to include the

byargument. For example:inner_join(df1, df2, by = c("df1_colname" = "df2_colname"))

Tidyr

The purpose of Tidyr is to have well-organized or tidy data, which Tidyverse defines as having:

- Each variable in a column

- Each observation in a row

- Each value as a cell

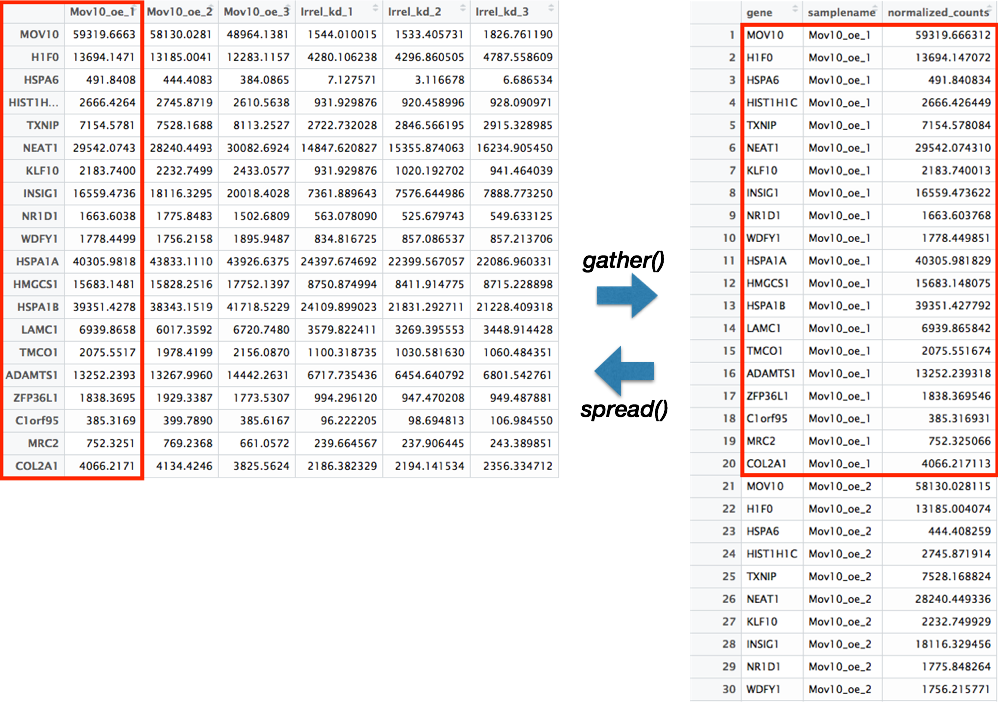

There are two main functions in Tidyr, gather() and spread(). These functions allow for conversion between long data format and wide data format. The downstream use of the data will determine which format is required.

gather()

The gather() function changes a wide data format into a long data format. This function is particularly helpful when using ‘ggplot2’ to get all of the values to plot into a single column.

To use this function, you need to give the columns in the data frame you would like to gather together as a single column. Then, provide a name to give the column where all of the column names will be present using the key argument, and the name to give the column where all of the values will be present using the value argument.

rpkm_data_tb <- rpkm_data %>%

rownames_to_column() %>%

as_tibble()

gathered <- rpkm_data_tb %>%

gather(colnames(rpkm_data_tb)[2:13],

key = "samplename",

value = "rpkm")

spread()

The spread() function is the reverse of the gather() function. The categories of the key column will become separate columns, and the values in the value column split across the associated key columns.

gathered %>%

spread(key = "samplename",

value = "rpkm")

Stringr

Stringr is a powerful tool for working with sequences of characters, or strings. While there are a plethora of functions in stringr that are useful for working with strings, we will only cover a those we find to be the most useful:

str_c()concatenates strings togetherstr_split()splits string by specifying a separatorstr_sub()extracts characters from a string at specific locationsstr_replace()replaces a string with another stringstr_to_()group of functions that change the case of the strings, includesstr_to_upper(),str_to_lower(), andstr_to_title()str_detect()identifies whether a pattern exists in each of the elements in a vectorstr_subset()returns only those elements that match a pattern

To help with using these functions in addition to other stringr functions there is a handy stringr cheatsheet.

str_c()

The str_c() function concatenates values together with a designated separator. There is also a collapse argument for whether to collapse multiple objects to a single string.

metadata <- metadata %>%

mutate(sample = str_c(genotype, celltype, replicate, sep = "_"))

str_split()

In contrast to str_c(), str_split() will separate values based on a designated separator.

metadata %>%

pull(sample) %>%

str_split("_")

str_sub()

For extracting characters from a string, the str_sub() function can be used to denote which positions in the string to extract:

metadata %>%

pull(sample) %>%

str_sub(start = 1, end = 8)

To replace a string with another string, the str_replace() function can be helpful:

str_replace()

metadata %>%

pull(celltype) %>%

str_replace("typeA", "typeP")

By default str_replace() will only replace the first encountered instance in each element/component. If you wanted to replace all instances, then there is the str_replace_all() function.

str_to_()

Frequently during data tidying we need to ensure that all values of the column have the same case, since R is case sensitive. An easy way to change the case of any value is to use the str_to_ family of functions, including str_to_upper(), str_to_lower(), and str_to_title().

metadata %>%

pull(genotype) %>%

str_to_upper()

metadata %>%

pull(genotype) %>%

str_to_lower()

metadata %>%

pull(genotype) %>%

str_to_title()

The last two functions, str_detect() and str_subset() require a pattern to match. Often to specify patterns in strings, regular expressions (regexps) are used, which describe these patterns. When using regular expressions there are special characters that are useful to know, and details regarding these are available in the R for Data Science book and these materials from Duke, but we have listed some frequently used characters below:

".": matches every character (if wanting to match a literal., then need to escape it using\\.)"^characters": matches start of string"characters$": matches end of string"[characters]": matches any of characters inside the []"[^characters]": matches any of characters NOT inside the []"[A-z0-9]": matches any letter or number"*": matches zero or more times

str_detect()

The str_detect() function identifies whether a pattern exists in each of the elements in a vector. The function returns a logical value for whether element matches pattern for each element in vector.

idx <- str_detect(metadata$sample, "typeA_1")

# Allows for subsetting dataframes using the logical operators

metadata[idx, ]

str_subset()

To only return those values that match a pattern, the str_subset() function will extract only those values:

metadata %>%

pull(sample) %>%

str_subset("typeA_1")

Programming notes

Underneath the hood, tidyverse packages build upon the base R language using rlang, which is a complete rework of how functions handle variable names and evaluate arguments. This is achieved through the tidyeval framework, which interprates command operations using tidy evaluation. This is outside of the scope of the course, but explained in detail in the Programming with dplyr vignette, in case you’d like to understand how these new tools behave differently from base R.

Additional resources

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.