Approximate time: 45 minutes

Learning Objectives

- Learn about quality control considerations when preparing your ChIP-seq experiment

- Understand the need for positive and negative controls

- Discuss suggested guidelines for sequencing of ChIP-seq data

Experimental design considerations

When starting out with your experiment, there are many things to think about. We have highlighted some of the important points in the previous lecture and within this lesson, but we also encourage you to peruse the ENCODE guidelines and practices for ChIP-seq. Although it was published in 2012, much of the information is still very valid and used in practice today.

NOTE: When relevant, we include comparisons to CUT&RUN and ATAC-seq to demonstrate how guidelines change for the different assays.

Starting material

ChIP-seq

Ensure that you have a sufficient amount of starting material because the ChIP will only enrich for a small proportion. For a standard protocol, you want approximately 2 x 106 cells per immunoprecipitation. If it is difficult to obtain that many samples from your experiment, consider using low input methods. Ultimately, higher amounts of starting material yield more consistent and reproducible protein-DNA enrichments.

Can I pool samples if I don’t have enough cells?

We generally recommend that you try to steer clear of pooling (for ChIP-seq and other NGS applications). There is variability between samples and mixing them together can increase background noise and dilute signal. In the case where you have small amounts of starting material, we suggest using CUT&RUN.

Click here for CUT&RUN guidelines

It is recommended to start with 500,000 native (unfixed) cells, particularly when mapping new targets or using new cell types. Following initial validation of workflows using 500,000 cells and control antibodies, cell numbers can be reduced (as low as 5K cells).

Click here for ATAC-seq guidelines

For ATAC-seq the requirement of cell number ranges from 50K to 500K.

Quality control of your ChIP

Your ChIP experiment is only as good as your antibody! The more specific the antibody, the more robust and accurate your results will be. Antibody deficiencies are of two main types: poor reactivity against the intended target and/or cross-reactivity with other DNA-associated proteins. Here, we boil it down to the following key points:

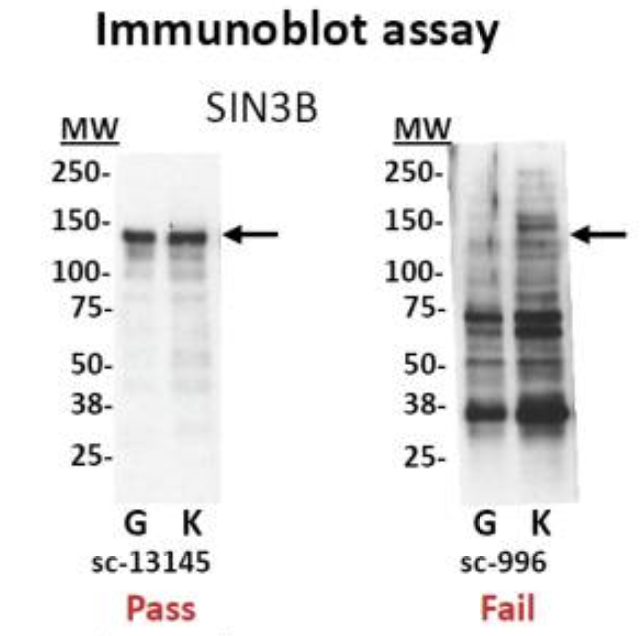

- Test your antibody with the use of a Western blot. These are performed on protein lysates from either whole-cell extracts, nuclear extracts, chromatin preparations, or immunoprecipitated material. Numerous antibodies have been shown to work in ChIP; nevertheless, it is best to test the antibody with the specific set of cells that you are working with.

Immunoblot analyses of antibodies against SIN3B that (left) pass and (right) fail quality control. Lanes contain nuclear extract from GM12878 cells (G) and K562 cells (K). Arrows indicate band of expected size of 133 kDa. [Landt et al, 2012]

- Check a few regions by qPCR to confirm that the pull-down worked. Create primers for regions of the genome you expect your protein of interest to bind. The PCR is performed on the immunoprecipitated material, before sending it for sequencing.

- You can also check a region of DNA that you do not expect to be enriched and thus do not expect to be amplified by qPCR, to show that your ChIP is specific (negative control)

Note that you cannot do a qPCR on a CUT&RUN library, the fragments are too short. See below for a positive control option instead.

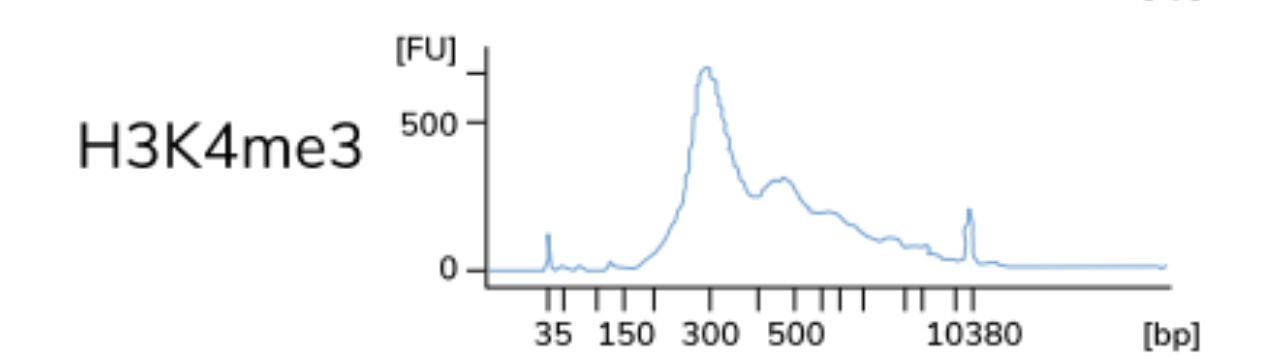

- If you don’t have any known targets for your protein, run a postive control ChIP. Histone H3 or H3K4me3 usually work very well. Since there is loads of H3K4me3 present at most TSSs you could design primers against the promoter of a housekeeping gene. If you have a good signal present, you will at least know the protocol is working well.

Should I test the efficacy of the CUT&RUN protocol?

A control CUT&RUN with an antibody against a histone mark is recommended, to assess protocol efficacy. After quantifying purified DNA, the fragments (50-150 bp) may not show up on the bioanalyzer electropherogram due to the low concentration of DNA present. With the control histone mark CUT&RUN, you should see mono-, di-, and tri-nucleosomes in the Bioanalyzer traces as shown below.

NOTE: The authors of this study also included a positive control sample using an antibody against p300 to test the protocol, although the data is not included here. The p300 protein has been shown to have binding sites in the cortex.

Negative Controls

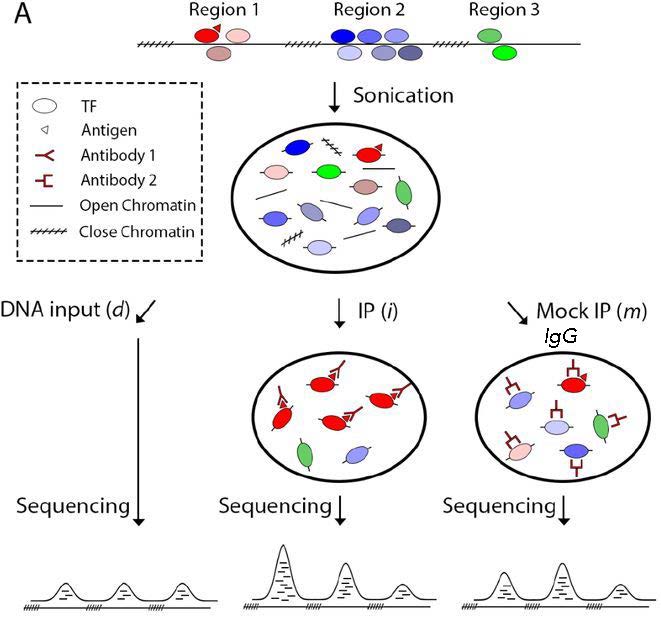

A ChIP-Seq peak should be compared with the same region of the genome in a matched control sample because only a fraction of the DNA in our ChIP sample corresponds to actual signal amidst background noise.

There are a number of artifacts that tend to generate pileups of reads that could be interpreted as a false positive peaks. These include:

- Open chromatin regions that are fragmented more easily than closed regions due to the accessibility of the DNA

- The presence of repetitive sequences

- An uneven distribution of sequence reads across the genome due to DNA composition

- ‘hyper-ChIPable’ regions: loci that are commonly enriched in ChIP datasets. Certain genomic regions are more susceptible to immunoprecipitation, therefore show increased ChIP signals for unrelated DNA-binding and chromatin-binding proteins.

There are two kinds of controls that can be used for ChIP-seq: IgG control and input control.

Image source: Xu J. et al., BioRxiv (2019).

IgG control is DNA resulting from a immunoprecipitation with an isotype-matched control immunoglobulin. An isotype control is an antibody that maintains similar properties to the primary antibody but lacks specific target binding. Save 5-10% of your cell lysate, and add the appropriate non-specific IgG instead of protein-specific antibody, but at the same concentration. This will give an indication of the assay background and identify non-specific binding of the beads used for the immunoprecipitation. However, if too little DNA is recovered after immunoprecipitation, the sequencing library will be of low complexity and binding sites identified using this control could be biased.

Input control is DNA purified from cells that are cross-linked, and fragmented, but without adding any antibody for enrichment. Save 5-10% of your cell lysate before addition of antibodies. Input samples can account for variations in the fragmentation step of the ChIP protocol as certain regions of the genome are more likely to shear than others based upon their structure and GC content. Input controls are more widely used to normalize signals from ChIP enrichment.

Do I need to have one input sample for each IP sample in my dataset?

The ENCODE guidelines [Landt, et al, 2012] states “If cost constraints allow, a control library should be prepared from every chromatin preparation and sonication batch, although some circumstances can justify fewer control libraries. Importantly, a new control is always performed if the culture conditions, treatments, chromatin shearing protocol, or instrumentation is significantly modified.”

The short answer is, yes having an input sample matched with each IP is ideal. However, studies have shown input replicates to have strong reproducibility in some cases. Thus, if there are constraints with budget or obtaining enough sample, having one input per sample group can suffice.

Do we need controls for CUT&RUN?

Similar to ChIP-seq, only a fraction of the DNA in a CUT&RUN sample will correspond to actual signal amidst background noise. Rather than having an input DNA control, the use of a nonspecific rabbit IgG antibody is recommended by the Henikoff lab. It will randomly coat the chromatin at low efficiency without sequence bias. While a no-antibody input DNA sample will generate a more diverse DNA library, the lack of tethering increases the possibility that slight carryover of pA-MN will result in preferential fragmentation of hyperaccessible DNA.

There is also an opinion that perhaps input control is more appropriate. One can argue that the IgG sample typically contains extremely small amounts of DNA and is not a good indicator for how well your target-specific antibody is working in the assay. Ultimately it may be best to go with whatever is recommended by the maker of the kit being used.

Do we need controls for ATAC-seq?

In ATAC-seq, you do not have a control. Intuitively, one might think we need to correct the bias caused by the Tn5 transposase. However, the original studies show that the intrinsic cutting preference/bias of the transposon is minimal and so controls are not neccessary.

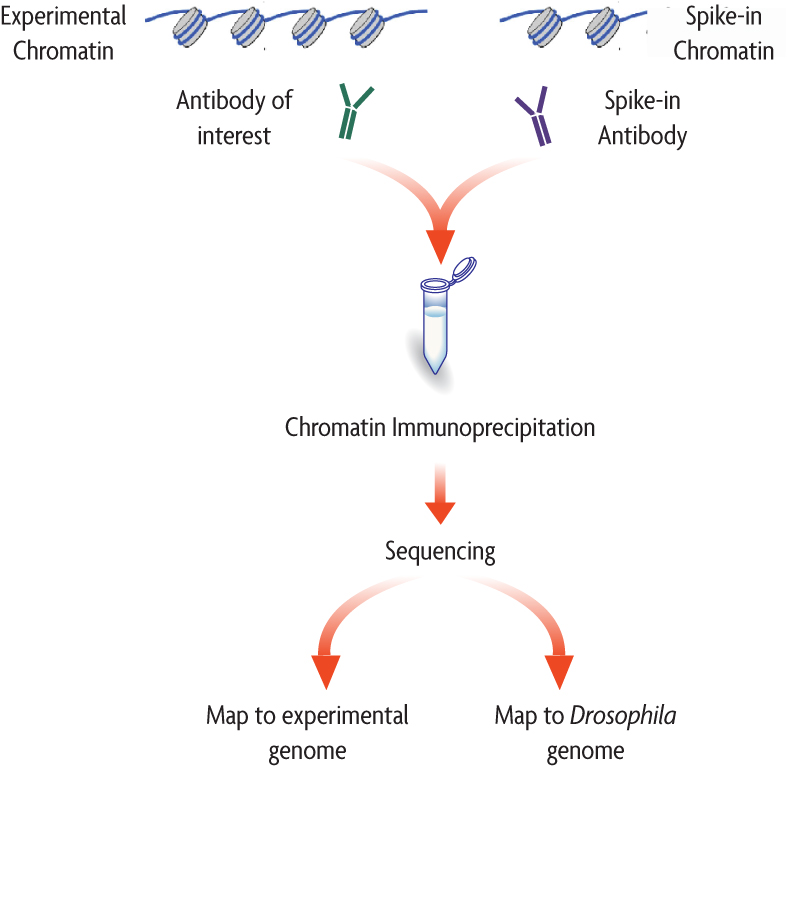

Spike-in DNA

There are multiple sources of technical variability that can hamper the direct comparison of binding signal strength between different conditions (in both, ChIP-seq and CUT&RUN data). For example, an increase in genomic occupancy of a chromatin factor could simply be the result of variability in the efficiency of immunoprecipitation between control and treated samples in a ChIP experiment.

The spike-in strategy is based on the use of a fixed amount of exogenous chromatin from another species that is added to sample in an effort to control for technical variation. Since we are adding a known amount (and the same amount) to each sample, we expect the number of mapped reads to the reference (in the example below, Drosophila) to also be similar.

Image source: Adapted from ActiveMotif documentation

- If the number of mapped reads to the spike-in reference are roughly the same across samples, then the observable differences in the reads of the experimental samples across conditions can be exclusively attributed to biological variation.

- There is no normalization required.

- If the number of mapped reads to the spike-in reference are variable across samples, this suggests that there is some amount of technical variation.

- A normalization factor can be computed.

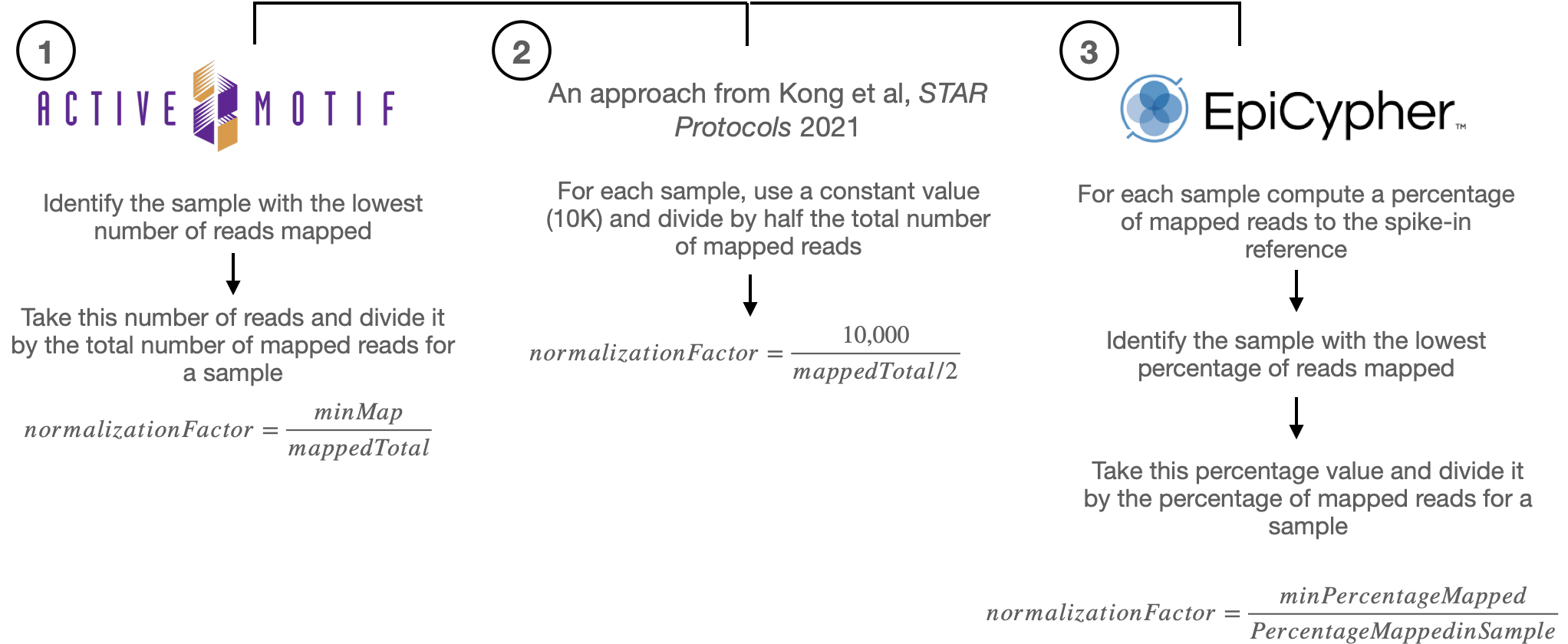

There are various approaches to computing the normalization factor, we have outlined some of them below:

The per-sample normalization factor computed from either of the three approaches, equilibrates the spike-in signal among samples. That same factor from is then used to normalize the experimental ChIP-seq samples (which in theory exhibit the same amount of technical variation), thus enabling the fair comparison of the ChIP-seq signal across the samples.

When should I use spike-in normalized data?

It is important that you qualitatively assess the data, because the normalization is only as good as the spike-in that was administered. The percent of reads mapping to the spike-in is typically 1% and no greater than 5%. A range is to be considered, because there is always a chance of human error due to the variability in protocols. After normalizing data with spike-in DNA, we typically recommend that you evaluate and make and informed decision whether or not to include it in your analysis.

References for spike-in normalization

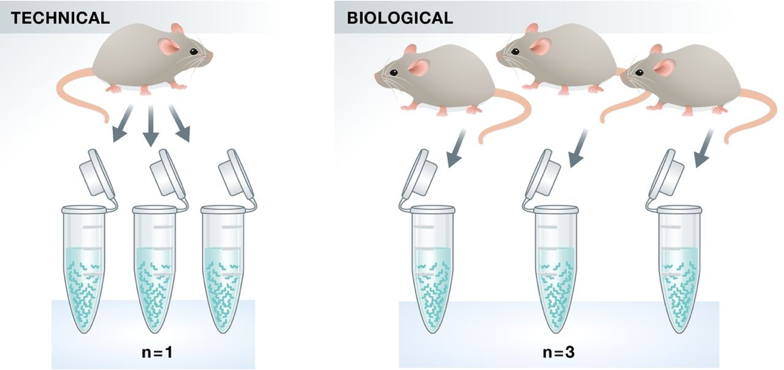

Replicates

As with any high-throughput experiment, a single assay is often subject to a substantial amount of variability. Thus, it is highly recommended to setup your experimental design with a minimum of 3 biological replicates. Presumably, two replicates measuring the same underlying biology should have high consistency but that is not always the case. Having replicates allow you to evaluate concordance of peaks and identify a set of reproducible enriched regions with greater confidence. If you have multiple sample groups and are planning a differential enrichment analysis, increasing the number of replicates will give you more statistical power to find changes between groups.

NOTE: Replicates are necessary for both CUT&RUN and ATAC-seq, for all of the reasons described above.

Image source: Klaus B., EMBO J (2015) 34: 2727-2730

Do we see batch effects in ChIP-seq data?

Typically, batch effects are not as big of a concern with ChIP-seq data. However, it is best to run everything in parallel as much as possible. If you only have a single sample group, it should be more feasible to prepare all samples together (since there are fewer). For multiple sample groups, if you are not able to process all samples together, split replicates of the different sample groups across batches. This way you avoid any potential confounding.

Sequencing considerations

| ChIP-seq | CUT&RUN | ATAC-seq | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read length | 50-150 bp | 50-75 bp | 50-75 bp |

| Sequencing mode | Single-end reads are sufficient in most cases. Paired-end is good (and necessary) for allele-specific chromatin events, and investigations of transposable elements. Sequence the input controls to equal or higher depth than your ChIP samples. | Paired-end reads are recommended to retain fragment size information. It also is allows us to more accurately obtain the minimal protein protected region after MNase digestion. | Paired-end is used to obtain fragment size information, useful for quality metrics and nucelosomal positioning. It also gives more information on the Tn5 cutting sites. |

| Sequencing depth | For standard transcription factors we recommend between 20-40 million total read depth | For most targets (narrow or broad profiles), 3-8 million paired-end reads are sufficient. | 50 million for changes in chromatin accessibility; 200 million for TF footprinting |

| Sequencing depth (broad peaks) | A minimum of 40M total read depth; more is better for detecting some histone marks | N/A | N/A |

NOTE 1: Balance cost with value of more informative reads. For example, if you have the money then spend it on replicates. This is more beneficial than longer reads or paired-end (in th ecase of ChIP-seq).

NOTE 2: The sequence depth guidelines are for mammalian cells. Organisms with smaller genomes will generally tend to have lower depth.

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.