Approximate time: 45 minutes

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast three methods for investigating chromatin biology: ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, ATAC-seq

- Understand the signal profiles that result from each method

- Review some popular public resources for accessing functional genomics data

Unraveling the epigenetic landscape

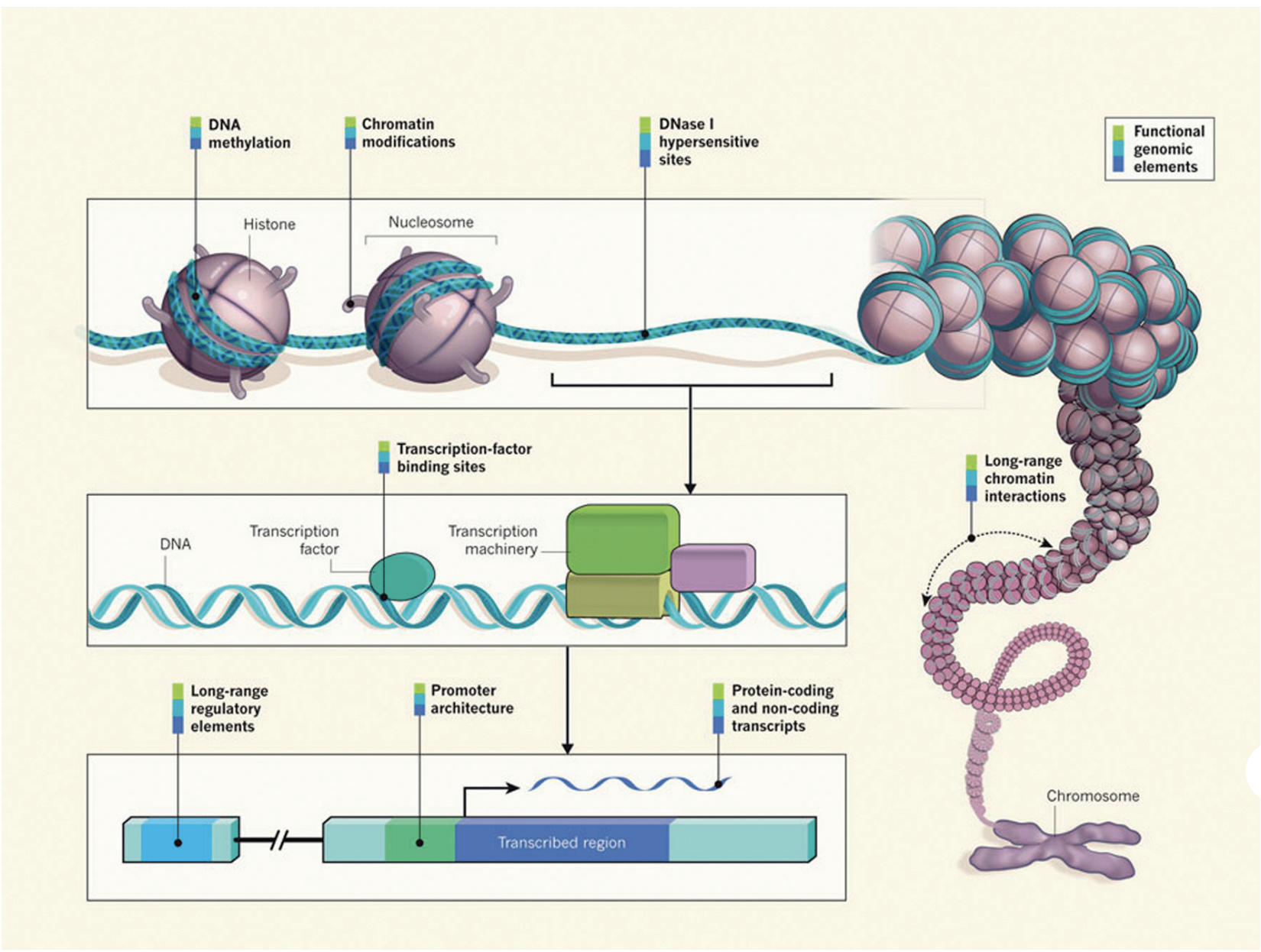

It is clear that DNA sequence and transcription factor availability alone are not sufficient for effective gene regulation in eukaryotes. Epigenetic factors at various levels also have an essential role. DNA wraps around histones to form nucleosomes, which fold and condense to form chromatin. In the processes of DNA replication and transcription, some regions of chromatin are opened and regulatory machinery can bind to the exposed DNA binding sites. In addition, the chromatin structure can undergo dynamic epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, histone modification and chromatin remodelling.

All of this together is critical for gaining a full understanding of transcriptional regulation.

Image source: “From DNA to a human: What the ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenome Projects can teach us about how we are who we are”

ChIP-seq: A method for detecting and characterizing protein–DNA interactions

In this workshop we will be focusing on the ChIP-seq technology. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a central method in epigenomic research. In ChIP experiments, a transcription factor, cofactor, or other chromatin protein of interest is enriched by immunoprecipitation from cross-linked cells, along with its associated DNA. The immunoprecipitated DNA fragments are then sequenced, followed by identification of enriched regions of DNA or peaks. These peak calls can then be used to make biological inferences by determining the associated genomic features and/or over-represented sequence motifs.

Image source: “From DNA to a human: What the ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenome Projects can teach us about how we are who we are”

ChIP-seq has been widely used for many transcription factors, histone modifications, chromatin modifying complexes, and other chromatin-associated proteins in a wide variety of organisms. As such, there is much diversity in the way ChIP-seq experiments are designed and the way analyses are executed.

CUT&RUN: An improved alternative to ChIP-seq

ChIP-seq is a notoriously challenging approach. Despite rigorous optimization and washing, the method is subject to high background. The resulting low signal to noise ratio makes it difficult to identify true binding sites.

Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) is an innovative chromatin mapping strategy that is rapidly gaining traction in the field. The protocol requires less than a day to go from from cells to DNA, and can be done entirely on the benchtop using standard equipment that is already present in most molecular biology laboratories.

How does it work?

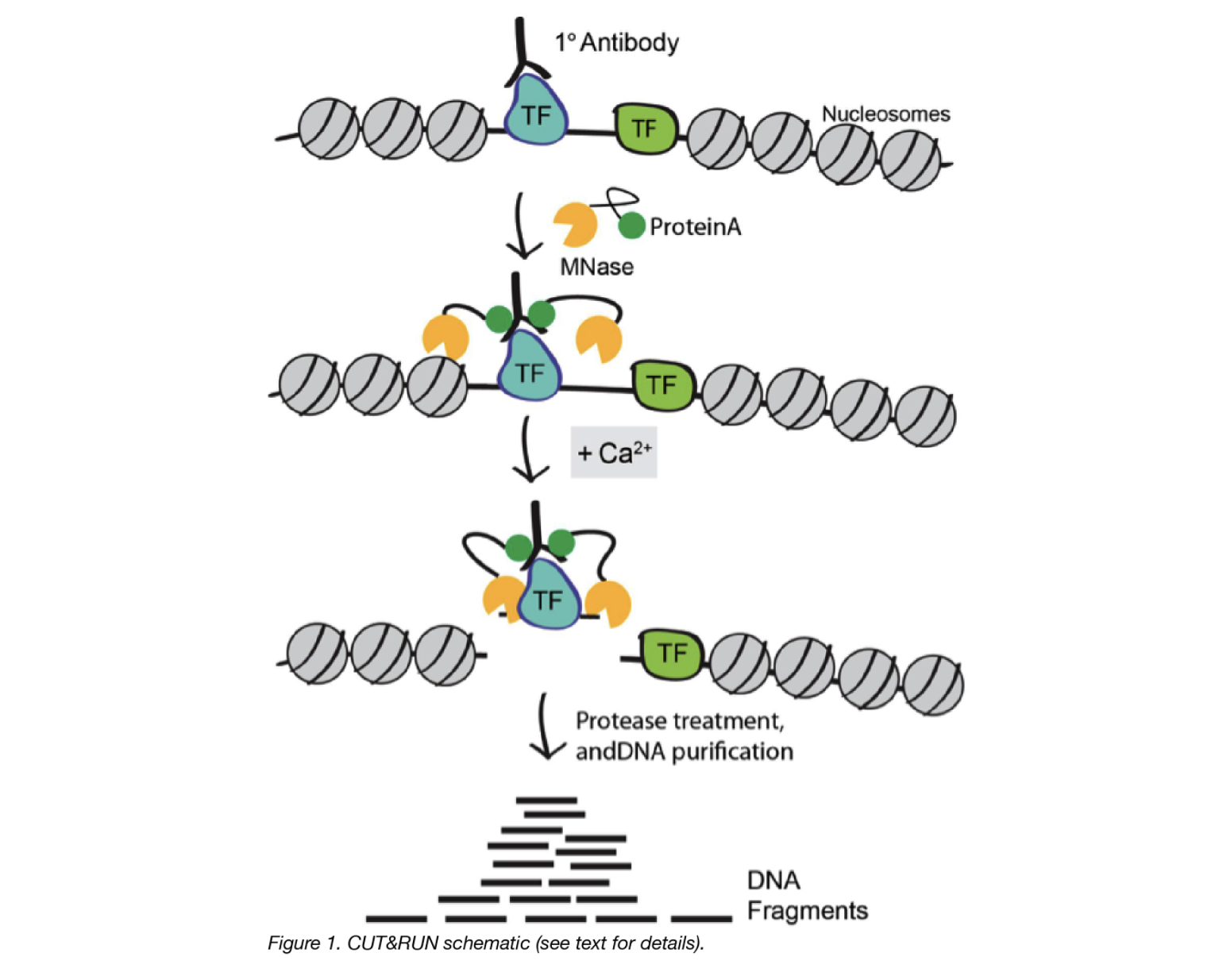

CUT&RUN is a native endonuclease-based method based on the binding of an antibody to a chromatin-associated protein in situ and the recruitment of a protein A-micrococcal nuclease fusion (pA-MN) to the antibody to efficiently cleave DNA surrounding binding sites.

Click here for more specifics on the CUT&RUN protocol

Below we describe each step of the protocol in some detail:

1. Cells/nuclei are bound to concanavalin A–coated magnetic beads.

In the original Henikoff lab paper they isolate nuclei. Using purified nuclei allows for maximal binding of antibodies to nuclear factors and will result in cleaner CUT&RUN signal compared to protocol using whole cells.

In the more recent paper, also from the Henikoff lab, whole cells are harvested. They introduce the use of a strong detergent to permeabilize cells rather than relying on the extraction of nuclei.

2. Cell membranes (or nuclear membrances) are permeabilized with digitonin to allow the antibody access to its target (1h to overnight)

3. The Protein A fused MNase is then added. Protein A binds the Immunoglobulin G (IgG) on the primary antibody (or mock IgG) thus targeting the MNase to antibody bound proteins.

4. The nuclease is briefly activated to digest the DNA around the target protein. This targeted digestion is controlled by the release of (previously chelated) calcium, which MNase requires for its nuclease activity. The nuclease reaction is performed on ice, and only for a short period of time, thus precisely controlling the amount of cutting and thereby mitigating noise generated by off target digestion.

5. At this point mononucleosomal-sized DNA fragments from a different organism is added (spike-in DNA).

6. Fragments are released from nuclei by a short incubation at 37 °C.

7. These short DNA fragments are then purified for subsequent library preparation and high-throughput sequencing.

Image source: “AddGene Blog”

What about CUT&TAG?

For the Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation assay, pAG is fused to a hyperactive Tn5 transposase (pAG-Tn5) pre-loaded with sequencing adaptors, and is activated by magnesium to simultaneously fragment and “tag” antibody-labelled chromatin with adaptors. This bypasses traditional library prep steps and accelerates sample processing. However, it only works well with nuclei.

Both assays were developed in the laboratories of Dr. Steven Henikoff (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA) and Dr. Ulrich Laemmli (University of Geneva, Switzerland).

CUT&RUN versus ChIP-seq

| Advantages of CUT&RUN | Limitations of CUT&RUN |

|---|---|

| Requires less starting material (smaller number of cells). | Not all proteins have been optimized for the protocol. You may need to invest time in pilot experiments to get the protocol working for you. |

| Lower depth of sequencing. | Likelihood of over-digestion of DNA due to inappropriate timing of the Calcium-dependent MNase reaction. |

| Background is significantly reduced, using targeted release of genomic fragments. | It is possible that a chromatin complex could be too large to diffuse out or that protein–protein interactions retain the cleaved complex. |

| Lower costs, by reducing antibody usage, library prep, and sequencing depth requirements |

ATAC-seq: Assaying open regions in the genome

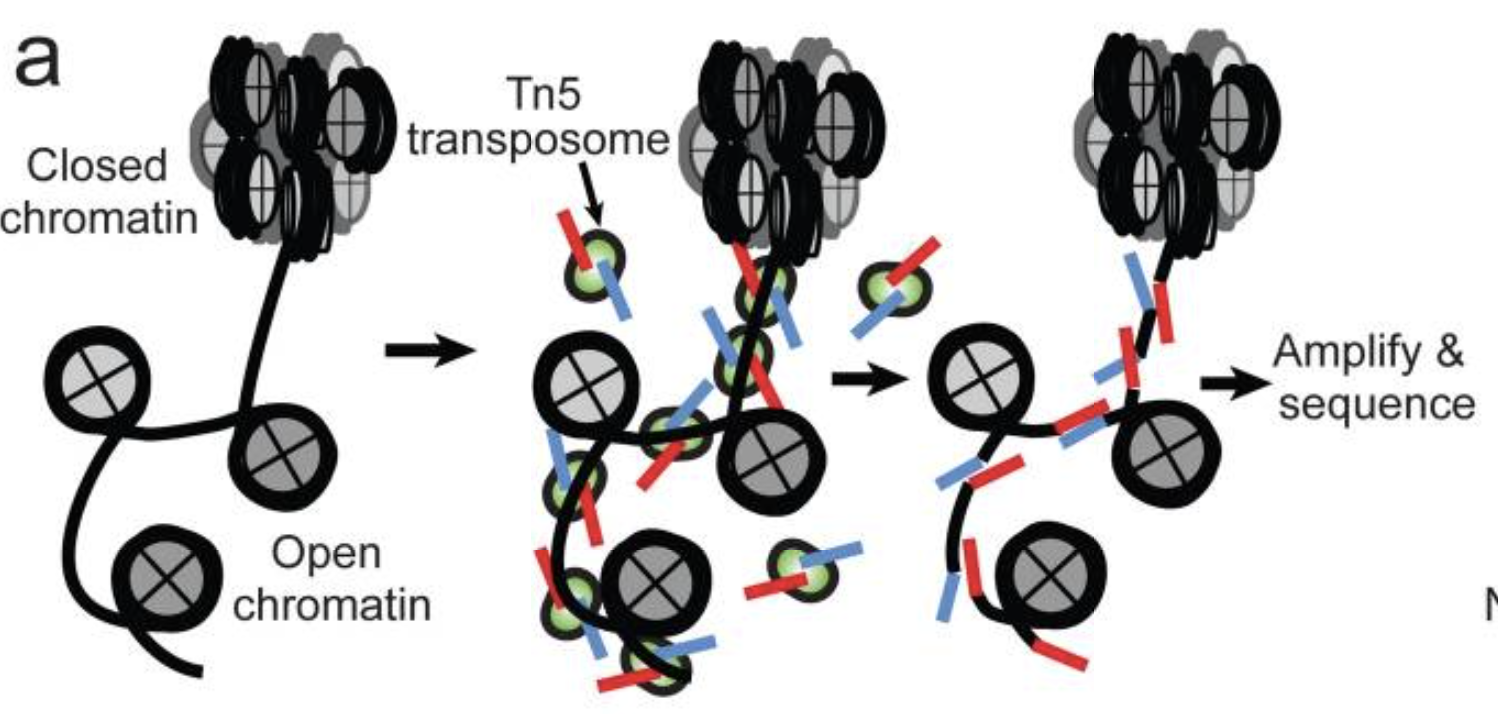

A popular approach used to identify open regions of the genome is the Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin (ATAC) followed by high throughput sequencing. The ATAC-Seq method was first published in 2013 in the journal Nature Methods by lead researcher Jason Buenrostro in the labs of Howard Chang and William Greenleaf at Stanford University.

How does it work?

- Utilizes hyperactive Tn5 transposase to insert sequencing adapters into the open chromatin regions

- Tn5 tagmentation simultaneously fragments the genome and tags the resulting DNA with sequencing adapters

- Amplify and sequence

Image source: Buenrostro et al., 2015

The method relies on the hyperactive Tn5 transposase that was already being used for tagmentation-based NGS library preparation methods. The authors hypothesized that if a similar approach was used in vivo, the addition of the adapters would mainly take place in open chromatin regions, where no steric hindrance of the transposase would occur, allowing the enzyme to preferentially access these regions.

Why ATAC-seq?

- The main advantage over existing methods is the simplicity of the library preparation protocol:

- Tn5 insertion followed by two rounds of PCR.

- no sonication or phenol-chloroform extraction like FAIRE-seq

- no antibodies like ChIP-seq

- no sensitive enzymatic digestion like MNase-seq or DNase-seq

- Short time requirement. Unlike similar methods, which can take up to four days to complete, ATAC-seq preparation can be completed in under three hours.

- Low starting cell number than other open chromatin assays (500 to 50K cells recommended for human).

Profiling chromatin structure

Protein-DNA binding

In a typical primary ChIP-seq analysis pipeline, the sequence reads are mapped to a reference genome and areas with the highest coverage (peaks) are determined. When we visualize the reads in a genome viewer these regions present with a characteristic signal profile depending on the protein of interest.

- Narrow peaks: a signal profile spanning a small region but with high amplitude (shown in the red track in the image below). The narrow peak profile is generally observed for most transcription factors, but also for some regulatory elements (i.e. CTCF).

- Mixed peaks: are more difficult to discern, as the profile is a mixture of narrow and broad. The example shown below is RNA polymerase II (orange), which has a sharp peak followed by a broader (lower amplitude) region of enrichment.

- Broad peaks: present as larger regions of enrichment across the gene body, and are typically observed with speicific histone marks as described below.

Image adapted from: Park P., Nature Reviews Genetics (2009) 10: 669–680

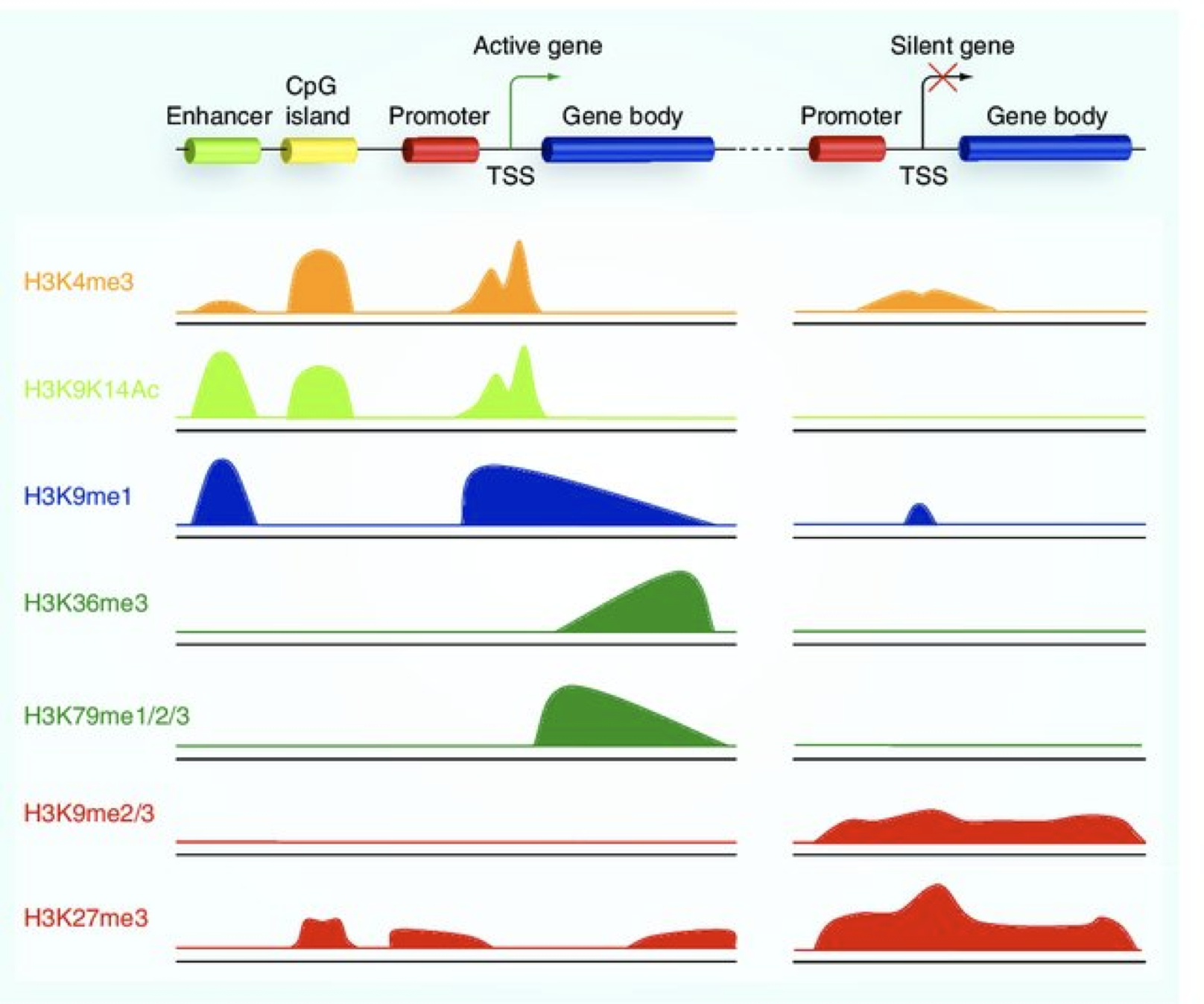

Histone modifications

When it comes to analyzing histone modifications, the histone code has the potential to be massively complex with each of the four standard histones possibly being modified at multiple sites with different modifications in their N-terminal ends. But in practice, researchers tend to limit themselves to a few modifications on Histone 3 with well characterized roles in gene regulation:

- Active promoters (narrow peak): H3K4me3, H3K9Ac

- Active enhancers (narrow peak): H3K27Ac, H3K4me1

- Repressor (broad peak): H3K9me3 and H3K27me3

- Actively transcribed gene bodies (broad peak): H3K36me3

Image source: Lim et al, 2010, Epigenomics

Chromatin accessibility

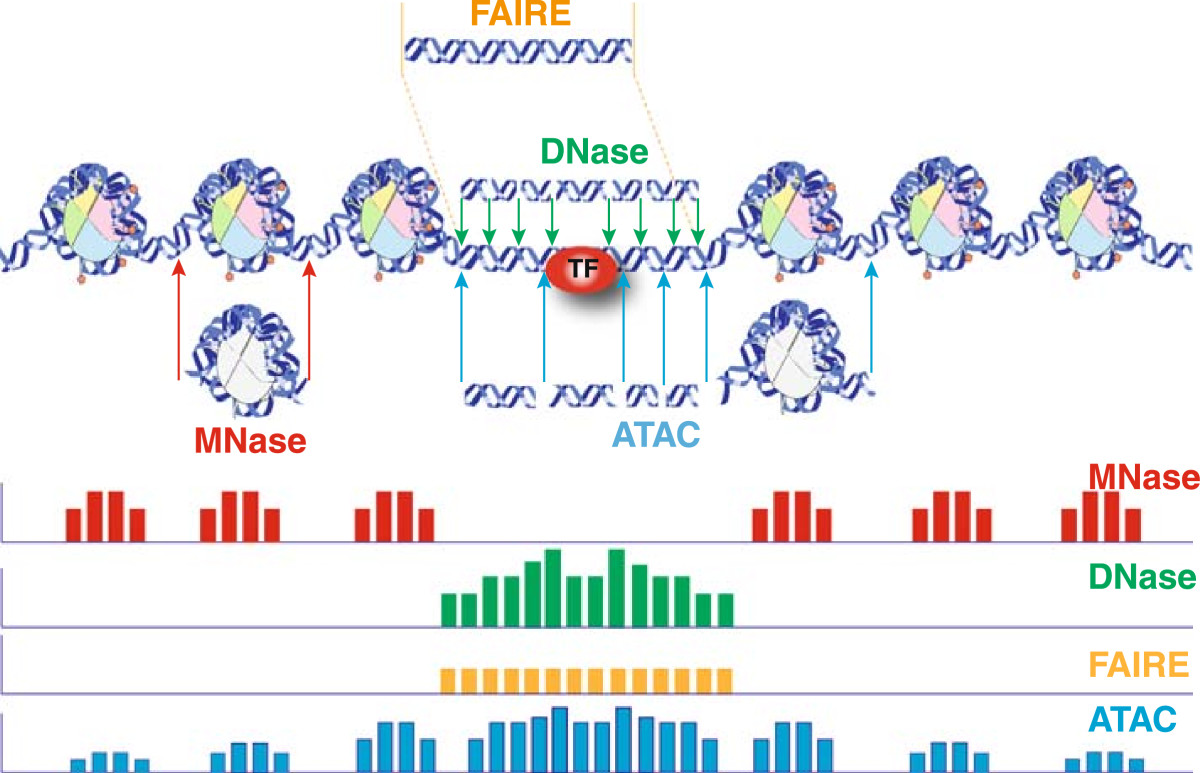

The schematic below illustrates the representative DNA fragments and the expected signal profile obtained from current chromatin accessibility assays.

- Open chromatin: FAIRE-seq, DNAse-seq

- Transcription factor occupancy: DNAse-seq

- Nucleosome occupancy: MNase-seq

In one assay, ATAC-seq is able to simultaneously assess three different aspects of chromatin architecture at high resolution. Therefore, in our data we will tend to see regions corresponding to the nucleosome-free regions (NFR) (< 100 bp) and mono-, di-, and tri-nucleosomes (~ 200, 400, 600 bp) respectively).

Image source: Tsompana and Buck, 2014

Public resources

The enormous amount of freely accessible functional genomics data is an invaluable resource for interrogating the biological function of multiple DNA-interacting players and chromatin modifications by large-scale comparative analyses. There are various consortia that have formed to collect data across studies and make it available to the research community. Ultimately, resources like this enable researchers to piece together the epigenomic landscape contributing to cell identity, development, lineage specification, and disease. We have described two popular resources below, but note that there are additional repositories in addition to various platforms developed for quick retrieval and comparative analysis.

The ENCODE project

The ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) Project was planned as a follow-up to the Human Genome Project. It is a public research consortium aimed to assign function to all elements in the human and mouse genome. Coinciding with the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, the ENCODE Project began as a worldwide effort involving more than 30 research groups and more than 400 scientists.

ENCODE has produced vast amounts of data that can be accessed through the project’s freely accessible database, the ENCODE Portal. The ENCODE “Encyclopedia” organizes these data into two levels of annotations: 1) integrative-level annotations, including a registry of candidate cis-regulatory elements and 2) ground-level annotations derived directly from experimental data.

NOTE: For those working on other model organisms, there is also the modENCODE (MODel organism ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) project, targeting the identification of functional elements in selected model organism genomes, specifically Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans.

NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium

The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Project has continued this journey, with a focus on human epigenomic data. This project was launched in 2008 with the goal of elucidating how epigenetic regulation contributes to human development and disease. The Roadmap Epigenome uses many of the same technologies used by ENCODE, but almost excusively focused on epigenetic features such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, while ENCODE emphasized identifying sites of DNA binding factor occupancy.

The data is presented as an atlas, where users can explore epigenome maps for stem cells and primary ex vivo tissues selected to represent the normal counterparts of tissues and organ systems frequently involved in human disease. Data can be viewed in the browser or downloaded locally.

This lesson has been developed by members of the teaching team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC). These are open access materials distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.